Enforcement spotlight – Autumn 2025

Europe’s enforcement of its digital rulebook reached another inflection point this season.

- Major penalties signaled regulatory teeth—Apple’s €500 million fine and Meta’s €200 million fine for DMA breaches show the Commission’s willingness to impose consequences.

- DSA enforcement also intensified[1], with 19 enforcement actions since May, dominated by efforts to protect minors online.

- The Commission opened four formal proceedings against adult platforms like Stripchat, XVideos, XNXX, and Pornhub in May over failures to safeguard minors from pornographic content, followed by four information requests in October targeting platforms including YouTube, Google Play, App Store, and Snapchat on minors’ protection and age verification.

But these actions happened while the regulations themselves came under threat.

The Commission’s Omnibus packages—ostensibly aimed at streamlining regulations—have become a battleground for Europe’s digital future, shaped by both internal and external pressures. These come as part of the Simplification Agenda, which claims to make[2] the EU faster, and more competitive—thereby improving implementation, and ensuring enforcement. But beneath these aims, the simplification agenda and the omnibuses in particular have become much more than a technocratic process.

Alongside this agenda, Brussels continues to fumble with digital sovereignty and thorny AI governance questions. On sovereignty, at the European Digital Sovereignty summit in Berlin in November, President Macron, Chancellor Metz, and Commission Vice-President Virkkunen discussed how to tackle Europe’s over-dependence on foreign digital infrastructure, posing major risks: from vulnerability to external disruptions—as the recent Amazon cloud outage[3] demonstrated—to threats to economic prosperity and even weakened enforcement leverage.

Meanwhile, on AI governance, the Commission unveiled multiple new strategies – the AI Continent Action Plan[4], Apply AI[5], and AI in Science[6] -while centering AI-friendly approaches in the simplification agenda.

Against this fraught backdrop, this third edition of the CFG Enforcement Spotlight examines how competing pressures are reshaping Europe’s digital enforcement landscape. What emerges is enforcement at a crossroads: brimming with potential to reshape Europe’s digital future yet increasingly vulnerable to fragmentation and coordinated political resistance. Whether Europe’s digital regulations will fundamentally reshape platform power or become words on paper depends on the central question of this edition. Who has the power to determine what enforcement means in practice?

Politics: What powers lie behind Europe’s enforcement choices?

This season, we saw that balance shifting in real time across multiple fronts. Public pressure for digital policy enforcement around elections clashed with industry and Member State demands for deregulation through “simplification,” while geopolitical pressure through trade negotiations and fracturing coalitions within Parliament itself reshaped enforcement priorities. These dynamics raise critical questions[7] about regulatory resilience: who controls enforcement and whether Europe’s regulatory ambitions can survive these competing pressures. This section examines how democratic resilience, simplification politics, and institutional fractures are determining the future of Europe’s digital enforcement landscape.

Testing the Digital Services Act (DSA) in elections

In the last spotlight, we discussed how “democratic processes have become a critical battleground for DSA enforcement.[8]” The topic continued to be significant, particularly regarding elections in Poland and Romania. Both elections served as a test, both of democratic resilience[9] and of the DSA’s capacity to protect electoral processes from platform-amplified harms. The results were mixed, as discussed below, revealing both the regulations’ potential when enforcement is targeted and limitations when systemic change is needed.

Public pressure proved critical in triggering effective DSA enforcement that strengthened democratic resilience around last year’s botched presidential election in Romania. When Romania’s election was annulled, people were furious about coordinated manipulation on TikTok. This pressure prompted the Commission to launch an investigation into TikTok—one of the major platforms under scrutiny alongside X for election integrity. Following this scrutiny, the Commission confirmed[10] that TikTok had strengthened election protection measures in Romania, including better political content labeling, adding 120 manipulation experts, activating the EU’s disinformation early warning system. Tiktok also launched an election center[11] offering verified election information, links to official sources, and a media literacy campaign in cooperation with local and EU authorities. The case demonstrates how the DSA can deliver results when public pressure compels both regulators to act and platforms to respond with substantive changes.

However, the regulation may not be producing the systemic behavioral change it was designed to achieve. In a new report[12] by the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, the DSA’s limitations are in focus. The study examined harmful content—including threats to election integrity and to officials such as election administrators—on Facebook from Polish and Lithuanian accounts, both before and after the DSA entered into force. Using AI models to classify posts from 2023 and 2024, researchers found no overall decline in harmful content following the DSA’s implementation, despite some platform-level improvements..

The European Digital Media Observatory’s report published in the summer, assessing the implementation of the Code of Practice on Disinformation—prior to its integration into the DSA framework— also reinforced[13] the contrast among very large online platforms (VLOPs) mentioned above, revealing uneven and partial compliance. While platforms such as Google and TikTok demonstrated stronger frameworks, Meta and Microsoft continued to lag behind in transparency and impact measurement.

The contrast is stark: Romania shows what’s possible when public awareness drives enforcement pressure, while the NATO and EDMO studies reveal what happens when that scrutiny fades—platforms reverting to baseline behaviors.

This exposes a fundamental challenge for democratic resilience: the DSA’s effectiveness in protecting electoral processes appears contingent on sustained public pressure rather than embedded in platforms’ default operations. If enforcement proves more effective with public backing, the critical questions become: how can regulators cultivate and harness public support for these laws in action? Can the public be built into the DSA’s enforcement pipeline more systematically—not just reactively during crises, but proactively as a permanent accountability mechanism?

Is simplification better enforcement—or regulatory capitulation to power?

The European Commission has framed its Omnibus simplification agenda as a “Better Regulation” effort aimed at making rules more efficient, coherent, and enforceable. Since the new Commission was formed, political priorities have centred[14] on making the EU simpler, faster, and more competitive by cutting red tape, improving implementation of EU laws, and ensuring enforcement when rules are not followed. Through its horizontal “Simpler and Faster Europe” agenda priority, the Commission targets up to a 35% reduction in administrative burdens for SMEs, strengthens cooperation with Member States for better policy delivery, and enforces compliance to protect the Single Market and citizens’ interests. The Commission insists that the Omnibus packages would not chip away at core policy goals.

Yet beneath these technocratic aims, the simplification agenda has become much more than a technical process—revealing the EU walking a “fine line between simplification and deregulation[15].”

The simplification process has been shaped by both external and internal pressures that raise fundamental questions about whether these efforts will genuinely improve enforcement or dismantle regulatory ambitions.

External pressures

The simplification debate became more complex—and more troubling—when transatlantic tensions over digital regulation we discussed in the previous Enforcement spotlight[16] spilled directly into EU-U.S. trade negotiations.

During EU-U.S. trade talks, American negotiators flagged the Digital Markets Act (DMA) and Digital Services Act (DSA) as “non-tariff barriers[17]” and sticking points in negotiations. These regulations, which target the market power and content moderation practices of major platforms – many of them American companies – had become leverage points in trade discussions.

The EU said[18] these rules weren’t up for negotiation. The U.S. challenged[19] this claim. Meanwhile, the Commission’s swift capitulation on sustainability regulations[20]– delaying[21] Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) deadlines and potentially scaling back requirements after similar U.S. pressure – raises concern about whether digital rules would receive the same treatment.

Beyond U.S. pressure, the “stop the clock” drama tested how far the Commission was willing to stretch for industry demands as opposed to counter-arguments from civil society organizations and experts.

After the General Purpose AI (GPAI) Code of Practice was delayed past its 2 May 2025 deadline, around 50 European companies – including ASML, Philips, Siemens, and Mistral – demanded[22] a “two-year clock-stop” before August obligations took effect. Commissioner Henna Virkkunen signaled[23] openness to delays.

But a powerful counter-movement emerged. Nobel laureates Daron Acemoglu and Geoffrey Hinton, along with over 40 experts, urged[24] the Commission to hold firm. A coalition of 52 civil society organizations followed[25], reframing the debate: this wasn’t about practical implementation challenges, but about whether the Commission would cave to industry pressure at the first sign of resistance.

The Commission initially held the line[26], publishing[27] the GPAI Code less than a month before the 2 August 2025 deadline. Currently, twenty-seven companies – including Amazon, Google, Microsoft, OpenAI, and European firms like Aleph Alpha and Mistral AI – are listed[28] as signatories. However, with the Digital Omnibus, the Commission ultimately changed[29] its mind, fundamentally restructuring the AI Act’s implementation timeline: High-risk requirements for Annex III systems (employment, credit scoring, law enforcement) are delayed until December 2027, while Annex I requirements (medical devices, product-based systems) are delayed until August 2028. The Commission retains discretion to accelerate timelines by 6-12 months once it deems standards “adequate.”

While the Omnibus proposal SMEs welcomed as “a step forward[30]” and framed[31] by the Commission as a playbook for growing European AI, legal and civic groups have raised serious concerns. Leaked drafts had already created backlash from political parties[32] to civil society[33] before the Commission’s final proposal arrived with full details. Once it was published and framed as pro-innovation, experts argued[34] that the idea that Europe “botched” AI by regulating “too much” is not entirely true, and that the political debate has been hijacked into a deregulation versus innovation fight—instead of focusing on productive issues like accessing capital, attracting and retaining talent, and market unification. To others[35], the current proposal makes AI enforcement much more complicated, setting aside fundamental rights concerns. We unpack the policy implications in detail below.

Internal challenges

Simplification has also faced internal challenges, including political fractures within Parliament and rhetorical shifts from Commission leadership itself.

While the Commission navigates external pressures, the European Parliament – traditionally a proponent of ambitious regulation – has become a site of internal fractures that threaten the very coalition that dominated Parliament for years and passed the laws now under simplification.

During negotiations over the first Omnibus package on sustainability, the European People’s Party (EPP) threatened to break with traditional centrist coalitions and align with far-right forces to push through tougher rollbacks. As lead negotiator for the sustainability Omnibus, EPP’s Jörgen Warborn stated: “It is very clear for all the political groups that the majorities have changed in the Parliament, and all the political groups have to adapt to the new reality.”

Although Socialists initially described the negotiations as “only threats and theater,” they ultimately caved[36] to center-right demands to slash EU green rules. The European Parliament adopted its position on Omnibus I with the European People’s Party choosing to align with the far right.

Not only in Parliament, but the Commission itself demonstrated an important semantic shift. Commission President von der Leyen declared[37] in her State of the European Union speech: “Europe is in a fight… A fight for our values and our democracies.” Just weeks later at the Copenhagen Competitiveness Summit, she dropped the semantic hedge that had characterized months of Commission communication, stating[38]: “We need simplification and deregulation and the Omnibuses should set the example.” What the Commission framed as technical “simplification” was now openly paired with “deregulation.”

Civil society and legal experts see something darker. To them, the Omnibus represents far more than semantic shifts—it undermines the democratic values von der Leyen vowed to protect. On content, they warn[39] it risks dismantling key protections that uphold fundamental rights in the digital age. On process, it features[40] impossible timelines that prevent proper parliamentary scrutiny, an EP that struggles to provide effective checks and balances, and the sidelining of meaningful public consultation. The European Ombudswoman reinforced these concerns last week, concluding[41] the Commission committed maladministration by failing to follow key Better Regulation procedures when preparing several urgent legislative proposals, undermining transparency, evidence-based law-making, and accountability. Rather than defending European democracies, the simplification agenda appears to risk hollowing them out.

As the centrist coalition that built the EU’s regulatory framework fractures and forces hostile to regulation gain leverage, the Commission’s own messaging has shifted from ‘simplification’ to openly embracing ‘deregulation.’ This raises a fundamental question: Is the Omnibus merely updating rules to reflect political reality, or does it represent a fundamental shift in the EU’s governance identity?

Policies: What is actually being enforced — and how it’s evolving

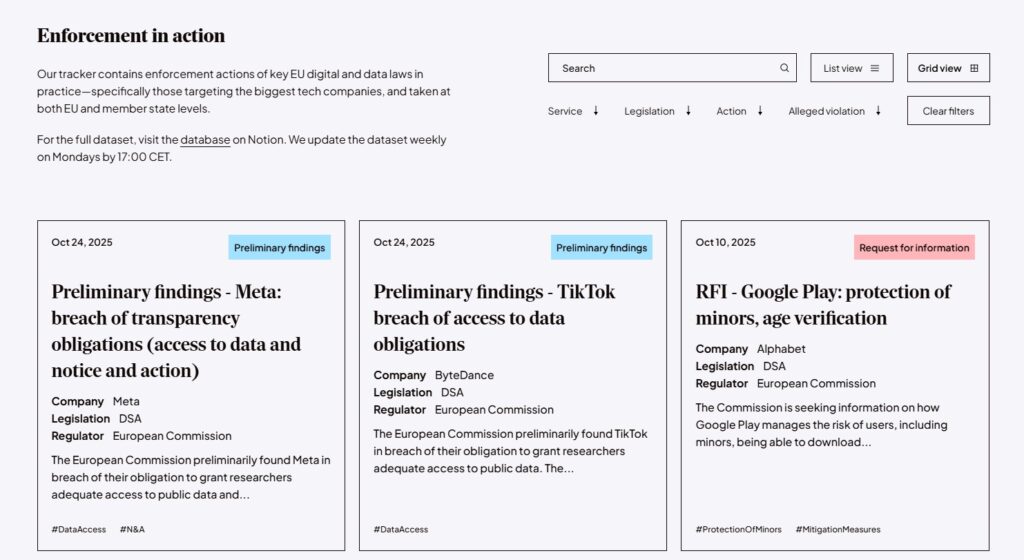

With insights from our new enforcement tracker[42], which gives an overview of the EU’s digital rulebook enforcement actions against big tech players, we’re seeing enforcement priorities take shape: opening investigations into platforms’ protection of minors and imposing substantial fines for DMA violations. Yet a striking disruption emerged recently with the Digital Omnibus Proposal. While scrutiny of LLM training practices under GDPR intensified this season, the Commission’s recent Digital Omnibus proposed fundamental changes to GDPR and the AI Act—redefining core GDPR concepts to benefit AI training, and delaying and weakening AI Act high-risk obligations. This section examines enforcement developments across GDPR, the AI Act, DSA, and DMA—showing how what gets enforced, when, and with what vigor ultimately determines whether Europe’s digital regulations reshape platform behavior or remain symbolic gestures.

GDPR

The Commission’s recent Digital Omnibus proposal also targets the GDPR with amendments including: modernising the definition of personal data in line with recent Court of Justice case law[43], clarifying when pseudonymised datasets can be shared, simplifying obligations on data protection impact assessments and breach notification, and overhauling cookie rules so users can reject cookies with one click and set central preferences in their browser.

However, civil society organizations criticised the proposed GDPR amendments. EDRi’s Itxaso Domínguez de Olazábal argued[44] that the proposal rewrites core GDPR concepts in ways that broadly expand what controllers may do—redefining personal data, easing the use of sensitive data for AI, weakening limits on automated decision-making, and adding new grounds to refuse transparency requests. Similarly, noyb[45] argued that contrary to the Commission’s official press release, the changes massively lower protections for Europeans.

One amendment—how legitimate interest applies to AI training data—stood out particularly in the context of recent discussions on LLM training data. Since LLMs have become ubiquitous and big tech companies compete aggressively for market share, questions about training data have generated significant enforcement debate. The GDPR already regulates data use in AI systems and remains the primary and most enforceable framework in this area. This season witnessed important developments on the subject.

For instance, Ireland—often considered the Achilles heel[46] of the EU’s pushback against Big Tech—became a crucial testing ground. In April 2025, the Irish DPA launched[47] an inquiry into X (formerly Twitter) over its use of publicly accessible EU/EEA user posts to train generative AI models, to assess compliance with GDPR requirements on lawfulness and transparency.

Scrutiny of LLM training data practices intensified with Meta. Noyb sent a cease-and-desist letter[48] to Ireland’s DPC to block Meta’s plan to use public user data for AI training in Europe, arguing it breaches GDPR by lacking valid consent. The Irish DPC reviewed[49] Meta’s updated plans to begin training its generative AI models, and required several improvements—including a simpler objection form and updated GDPR assessments, with Meta instructed to report on the effectiveness of these measures.

Civil society organizations also challenged Meta in Germany, where a consumer group filed for an injunction against Meta’s LLM training with EU user data. However, a German court declined[50] to grant an interim injunction against Meta, allowing it to proceed—at least for now—with using publicly available data to train AI models. The court found no immediate breach of the GDPR or the DMA, though the case remains open.

Despite civil society’s efforts to enforce the GDPR more strictly, the recent Digital Omnibus package proposes treating AI training as a legitimate interest and a compatible further use. According to noyb[51], this move normalizes the large-scale use of Europeans’ publicly available data without meaningful consent or compensation, effectively treating personal data as a free input for AI development. Similarly, Ada Lovelace[52] stated in their initial reaction that the Omnibus “effectively disapplies swathes of GDPR safeguards in the interests of AI development and use and alters the core presumption that people should have control over their own data.”

While the Commission presents the proposal as a playbook for scaling European AI, paradoxically it would largely benefit global firms that already have the capacity to train large models on this newly accessible data. As a result, the EU might risk weakening its own digital competitiveness by making Europeans’ data easier for foreign actors to exploit rather than using it to strengthen Europe’s own tech ecosystem.

AI Act

Since the last spotlight, the Commission unveiled ambitious strategies—the AI Continent Action Plan[53], Apply AI[54], and AI in Science[55]—to position Europe as a global leader. Yet AI Act enforcement remained mostly in a preparatory phase.

In anticipation of supporting effective implementation and providing legal certainty in a fast-moving AI market, the Commission launched[56] the AI Act Service Desk and the AI Act Single Information Platform. These services are a welcome addition to the AI Office. Their success will depend on whether they can genuinely facilitate compliance and give investors the clarity they need.

Preparatory efforts were not only at EU level but also at Member State level. The European Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ECNL) and the University of Utrecht developed[57] guidance to put Fundamental Rights Algorithmic Impact Assessments into practice—helping organizations make informed decisions about algorithmic benefits and potential human rights impacts, document decision-making processes, and build greater awareness of the ethical dimensions of algorithmic systems.

However, the most significant development for AI Act enforcement came with the Commission’s Digital Omnibus proposal, which fundamentally restructures implementation. Putting an end to the “stop the clock” debate over AI Act implementation, with industry demanding delays and civil society urging the Commission to hold firm, the Commission ultimately sided with industry. The Omnibus proposes[58] to delay high-risk requirements for Annex III systems (employment, credit scoring, law enforcement) until December 2027, and Annex I requirements (medical devices, product-based systems) until August 2028. Rather than providing clarity, the new timeline structure creates even more significant uncertainty.

First, the Commission retains discretion to accelerate timelines by 6-12 months once it deems standards “adequate.” As legal expert Dr. Barry Scannell identifies[59] the core problem: instead of knowing that high-risk obligations apply “next August,” companies now face the answer “sometime before December 2027.” But when will the Commission confirm necessary harmonized standards, common specifications, and support tools exist? “Nobody knows.”

Second, experts note[60] potential timeline chaos because it’s unclear whether the Omnibus will even be adopted before the original AI Act high-risk regime begins applying in August 2026. If negotiations extend beyond August 2026—a scenario that’s likely given the previous Omnibus negotiations took nine months just for a Parliament position —the EU enters uncharted legal territory where enforcement of high-risk infringements becomes technically possible during a window before the delay takes effect.

Beyond timeline changes, the Omnibus introduced[61] major substantive shifts that may undermine core AI Act protections: allowing providers to self-declare systems as non-high-risk, removing certain monitoring obligations, centralizing oversight in the AI Office, expanding sandboxes, and simplifying compliance for smaller companies. It also loosens rules on processing sensitive data for bias correction and shifts AI-literacy obligations from providers and deployers to governments.

While the European Digital SME Alliance welcomed[62] the reduced obligations for SMEs, seeing them as necessary relief, civic organizations and the conformity assessment industry flagged concerns: EDRi claimed[63] the Omnibus “tears the AI Act apart,” while TIC Council warned[64]that removing registration obligations weakens core safeguards and postponing provisions adds legal uncertainty—urging co-legislators to balance efficiency with consumer protection.

The stark divide in reactions reflects deeper tensions: implementation realities are complex, but regulatory simplification effectively weakens protections, substantively and procedurally. Companies now facing impossible questions about when obligations actually apply and whether investment in compliance now will prove premature or essential.

Digital Services Act (DSA)

This season, DSA enforcement prioritised protecting minors online. This enforcement focus reflects broader concerns about technology’s impact on youth mental health and wellbeing (also see our recent piece on emerging tech and emer

ging mental health risks[65]). With a spike in enforcement actions around minors online[66], from key investigations to comprehensive guidelines to new technical tools, the DSA enforcement ecosystem is stepping up to apply the regulation to its full potential for minors’ protection.

The European Commission opened[67] formal DSA investigations into Pornhub, Stripchat, XNXX, and XVideos over failures to protect minors, citing inadequate age verification, risk assessments, and safeguards. The Commission also expanded[68] its investigation into TikTok to address “SkinnyTok,” a harmful algorithm-driven trend promoting extreme thinness among minors. Following EU and French regulators’ concerns, TikTok globally banned[69] the hashtag and redirected searches to mental health support resources.

Alongside these investigations, the Commission also published[70] final DSA guidelines on the protection of minors in July 2025. The guidelines set out measures to protect children from grooming, harmful content, addictive behaviors, cyberbullying, and harmful commercial practices, recommending age verification methods to restrict access to adult content. To operationalize these guidelines, the Commission first started testing[71] its age verification app with five countries, linking it with the EU digital wallet (eID) for use on pornographic platforms and allowing other platforms to demonstrate compliance with Article 28 of the DSA. More recently, the Commission released[72] an enhanced second version of the age-verification blueprint, introducing additional features, such as the use of passports and ID cards for onboarding.

This progression, from investigations → guidelines → technical tools, reveals the Commission’s enforcement strategy: use high-profile cases to establish priorities, develop clear guidelines for compliance expectations, and provide tools that eliminate platforms’ excuses for non-compliance.

Yet these enforcement actions also reveal gaps in the existing digital rulebook. The forthcoming Digital Fairness Act aims to address blind spots in consumer protection online, particularly around dark patterns and manipulative design practices that affect minors in particular. CFG submitted[73] evidence as part of the public consultation on the Digital Fairness Act, highlighting how these protections would complement and strengthen DSA enforcement for better protection of vulnerable users.

Digital Markets Act (DMA)

DMA enforcement is transitioning from negotiations to concrete penalties.

The Commission’s annual report[74] highlighted enforcement focusing on platform business models: consent models, cross-service data use, data portability, and profiling. These aren’t technical compliance issues—they are fundamental business design practices that harm user privacy, competition dynamics, and market revenue generation. By targeting these core business practices, the Commission signals its willingness to use the DMA to tackle business models that undermine market fairness, even when doing so challenges platforms’ core revenue strategies.

Supporting this enforcement approach, the Commission demonstrated[75] willingness to impose substantial penalties this season. Apple was fined €500 million for anti-steering violations, and Meta €200 million for failing to offer users a less data-intensive service option. These decisions came after extensive dialogue, suggesting the Commission exhausted compliance negotiations before resorting to sanctions. Platform responses varied: Apple introduced new EU-specific measures[76] under Commission review, while Meta made limited adjustments[77] that the Commission indicated may not achieve full compliance—suggesting further enforcement may be necessary.

The DMA is also increasingly operating within a complex multi-regulatory environment, integrating with GDPR, competition law, and consumer protection. Following the annual report’s discussion of this integration, the Commission gathered[78] views on how the DMA can support fair and contestable digital markets in the AI sector, indicating it is staying its course with critical public and expert guidance.

Players: How do public and private actors shape the enforcement ecosystem?

Even the most carefully crafted policies are only as effective as the mechanisms and actors that enforce them. As the EU’s digital rulebook expands (or contracts, Omnibus-style), understanding who enforces these rules—and whether they have the resources, talent, and independence to do so—has become critical to determining whether Europe’s regulatory ambitions will succeed or falter.

This season we see a troubling pattern emerging: the enforcement ecosystem itself shows signs of serious strain—from staffing crises at the Commission to implementation failures across Member States. And looking ahead to more regulatory tumult, from the digital Omnibus to the AI Act coming into full force, this pattern will worsen if left unchecked.

The EU level

A capacity crisis at the Commission

The Commission’s workforce and expertise capacity is critical for effectively enforcing the EU digital rulebook. In our previous Spotlight[79], we highlighted persistent calls for increased personnel on DMA and the AI Act.

In response to these calls to address capacity challenges, we’ve seen the Commission give mixed signals. For DSA enforcement, the European Commission launched[80] a call to recruit 60 officers. This recruitment drive signals the Commission’s commitment to building a dedicated enforcement team for the DSA’s complex platform oversight requirements.

Around the corner, the Commission’s staffing situation for the DMA presents a genuine enforcement crisis. After earlier calls for more staff went unheeded, Olivier Guersent, head of the European Commission’s competition department, raised yet another alarm, this time with a stark warning[81] that severe understaffing is forcing the department into impossible trade-offs. With only 19 staff instead of the 80 planned for DMA supervision – a staggering 76% shortfall – the department cannot adequately oversee either new DMA priorities or traditional antitrust cases. When high-ranking officials sound such alarms publicly, it signals not just resource constraints but a fundamental threat to the Commission’s ability to enforce one of its flagship digital regulations against the world’s most powerful tech companies.

Closing definitional loopholes in The Parliament

Regulating powerful companies and their rapidly-evolving technologies requires burden sharing across Europe’s entire enforcement architecture. The European Parliament has demonstrated its role in this distributed enforcement model by identifying regulatory gaps before they are exploited.

With the collective call for action against “openwashing” mentioned above, 30 MEPs called[82] on the Commission to define what constitutes truly open-source AI. Without such clarity, companies can exploit definitional ambiguities to circumvent regulatory obligations, rendering enforcement efforts ineffective regardless of staffing levels.

This intervention illustrates the EuropeanParliament’s potential role as a regulatory watchdog—identifying loopholes that companies might exploit and pressing the Commission to close them before enforcement begins. This role is crucial and should be further supported by deepening existing dialogues between MEPs and experts—through STOA, the EPRS, and ad hoc hearings—so that they become more continuous, informed, and forward-looking.

An implementation gap for Member States

Effective EU-level enforcement depends on robust implementation at the national level—and vice versa. This season, we saw an implementation deficit widening across Member States. The European Commission has referred[83] Czechia, Spain, Cyprus, Poland, and Portugal to the EU Court of Justice for failing to fully implement the DSA by not properly designating or empowering their Digital Services Coordinators or setting penalty rules, while issuing a reasoned opinion to Bulgaria for similar shortcomings.

So far, no publicly documented remedial steps have been reported by the referred states. Earlier this year, civil society organisations had already signalled[84] uneven readiness among Member States, warning of multiple challenges at national level, including delays in passing national laws, resource shortages, recruitment difficulties, reliance on informal enforcement, and persistent structural weaknesses in independence, staffing, accountability, and funding.

This deficit undermines the entire digital enforcement ecosystem. Europe’s digital rulebook divides enforcement between EU institutions and Member States—the Commission oversees gatekeepers and very large platforms, while Member States handle other platforms and local enforcement. When Member State capacity fails, it creates a fundamental hole: EU-level enforcement functions while national-level enforcement does not. Companies can exploit weaker jurisdictions through compliance arbitrage, citizens remain vulnerable to non-compliance, and public trust in EU institutions and laws erodes. Without functioning national authorities, even successful Commission enforcement becomes isolated rather than part of a coherent EU-wide system.

Non-governmental players

Non-governmental players are as important as governmental players in holding up an effective digital enforcement ecosystem. Given capacity constraints at both EU and Member State levels, mobilizing independent expertise has become not just helpful but essential. This season we see the Commission actively working to mobilize independent expertise—and non-government organisations (NGOs) and experts are calling for more.

Independent researchers and practitioners

For the AI Act, the European Commission launched[85] a call for 60 independent experts to join the new AI Scientific Panel. This standing panel will advise the Commission’s AI Office and, where requested, national market surveillance authorities on how to govern general-purpose AI models, focusing on systemic risks, model classification, evaluation methodologies, and cross-border market surveillance.

On another front, the European Commission adopted[86] a delegated act under the DSA establishing rules for qualified researchers to access internal data from very large online platforms and search engines in order to study systemic risks. The act details data-sharing procedures, documentation requirements, and public information obligations for platforms and national Digital Services Coordinators. By empowering independent researchers to study and investigate platform practices, the Commission is effectively enhancing the EU’s digital policy enforcement capacity.

Member States are also activating trusted flagger mechanisms to enhance enforcement capacity. Germany’s Digital Services Coordinator designated[87] three new trusted flagger organizations under the DSA—the Federal Association of Online Retailers, HateAid, and the Federal Association of Consumer Organizations—each focusing on different areas, with their notifications of suspected illegal content prioritized by platforms for faster removal. Meanwhile, Ireland’s Central Bank became[88] the first Irish organization to receive Trusted Flagger status, designated by the national media regulator Coimisiún na Meán. These designations operationalize the DSA’s vision of distributed enforcement, enabling specialized organizations to contribute their expertise to content moderation oversight.

Beyond these formal integration mechanisms, civil society organizations have emerged as critical enforcement actors through monitoring, advocacy, and accountability pressure. The “stop the clock” mobilization mentioned above—where 52 organizations successfully pushed back against industry demands to delay AI Act implementation—demonstrated civil society’s capacity to counter corporate pressure at crucial moments. Similarly, organizations like Corporate Europe Observatory and EDRi filed formal complaints challenging conflicts of interest at the AI Office[89] and Ireland’s Data Protection Commission[90], working to prevent regulatory capture before it undermines enforcement.

International civil society also convened high-profile events like the “Future of Democracy[91]” conference in Brussels, bringing together policymakers and advocates to coordinate on defending digital regulations against mounting political and industry pressure. At the event, Margrethe Vestager, who served as the EU’s Competition Commissioner for 10 years until 2024, urged the EU to stand its ground despite U.S. pressure and keep its promises to Europeans.

These initiatives—from formal roles as trusted flaggers and research partners to informal roles as watchdogs and advocacy coalitions—strengthen the EU’s overall digital enforcement ecosystem by adding complementary skillsets, increasing diversity of actors, and ensuring accountability of both companies and regulators themselves.

A shifting landscape for industry

As technology evolves rapidly, digital rules must be flexible enough to adapt to changing market dynamics and emerging players. This season we saw the industry landscape shift constantly.

As LLMs grow and become platforms offering services from search engines to marketplaces, big players like ChatGPT[92] could soon fall under the scope of the DSA as a Very Large Online. ChatGPT’s search feature reached an average of more than 120 million monthly EU users over the past six months—a figure that’s nearly triple the DSA’s 45 million threshold. If formally designated by the Commission, ChatGPT would become the first standalone AI service regulated under the DSA, setting a precedent for how AI-driven services will be regulated beyond the AI Act.

Yet despite ChatGPT tripling the designation threshold, regulators have struggled[93] to act swiftly—with a decision not expected until mid-2026, according to Commission officials. This sluggishness in applying the DSA to AI chatbots contrasts starkly with the boom in their use, raising questions about enforcement capacity when emerging technologies rapidly cross regulatory thresholds.

Conversely, the European Commission ended[94] Stripchat’s designation as VLOP under the DSA after confirming its EU user base stayed below the threshold for a full year, with the platform’s VLOP obligations ending in four months, though general DSA duties—such as protecting minors—will remain in force. Similarly, the European Commission decided[95] that Facebook Marketplace will no longer be designated under the DMA, concluding after Meta’s request and review that the platform no longer meets the threshold of 10,000 business users required to qualify as an important gateway for businesses to reach consumers.

Resources, structures, and political will

While we saw severe capacity constraints this season—particularly the DMA’s staffing shortfall—the EU and its Member States must seek longer-term opportunities to bolster and improve digital enforcement across the continent. The next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) represents Europe’s best near-term chance to address[96] these resource gaps systematically.

As we have already signaled[97], alongside several others[98], Europe needs a radical structural reform, such as an overarching Digital Enforcement Agency, in order to streamline fragmented and uneven enforcement efforts, and in order to stand taller and firmer against geopolitical and industrial headwinds.

Procedures: How does the enforcement ecosystem work—formally and informally?

Beyond formal proceedings and penalties, enforcement depends on a complex ecosystem of monitoring mechanisms, coordination structures, civil society pressure, and industry engagement—which can either facilitate compliance or create obstacles to enforcement. This season we’ve seen how these procedural elements can either strengthen or undermine enforcement effectiveness.

Monitoring and transparency mechanisms

Effective enforcement requires continuous monitoring of compliance, both by regulators and third-party watchdogs. This season, we observed monitoring operating through multiple channels, displaying varying degrees of effectiveness.

Annual reports like the DMA report mentioned above, which are co-produced by the European Commission and companies in scope of each law’s provisions, help keep track of the laws in practice. To maintain ongoing dialogue with public stakeholders and industry players in scope, the Commission held six DMA stakeholder workshops[99] this season spotlighting a different gatekeeper each time to discuss updates and stakeholder feedback on compliance measures. These and other workshops held by the Commission, on evolving themes like online advertising[100] or minors’ protection[101] under the DSA, serve a triple purpose:

- They create opportunities for companies to demonstrate good-faith compliance efforts;

- They give policymakers, regulators, and other enforcement players insights into where resistance or confusion persists;

- They create necessary space in enforcement procedures for public or independent expert consultation.

Independent monitoring also provides critical accountability checks. Reports from the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence[102] and the European Digital Media Observatory[103] revealed persistent gaps in platform compliance and content moderation effectiveness (see Democratic Resilience discussion in the Politics section).

CFG’s new enforcement tracker[104], a public dashboard documenting enforcement actions across all EU digital and data laws facing the biggest tech companies since June 2023, documented 23 enforcement actions over the last six months alone. These actions range from official proceedings to informal measures such as requests for information—illustrating the breadth of enforcement activity beyond the headline-grabbing fines.

Behind these monitoring mechanisms lies a fundamental challenge for regulators: companies may appear cooperative in workshops, yet independent monitoring and assessments—as shown in the examples above—reveal persistent non-compliance. This gap between public dialogue and actual behavioral change underscores the need for third-party monitoring as a prerequisite for enforcement—not as a substitute for enforcement. Effective monitoring and assessment can and must continue to inform where and how enforcement is to be applied, especially as the technologies in question evolve so rapidly.

Cross-border enforcement infrastructure

Enforcement cannot succeed without a functional cross-border infrastructure. This season, we saw both promising coordination efforts and persistent gaps in cooperation across Member States.

Seven out-of-court dispute settlement bodies created[105] a network to strengthen enforcement of users’ rights under the DSA, warning that despite receiving over 4,500 complaints in early 2025, most users remain unaware of their right to contest platforms’ content decisions. The network urged greater industry transparency and cooperation, highlighting how even well-designed enforcement mechanisms fail if users don’t know they exist or—worse—if platforms don’t cooperate.

More encouragingly, the European Board for Digital Services launched[106] coordinated action across Member States to strengthen protection of minors from pornographic content on smaller platforms. National authorities are sharing enforcement methods and best practices based on the forthcoming guidelines under DSA Article 28and on insights from the Commission’s ongoing investigations. This coordination represents the enforcement architecture functioning as designed—central guidance combined with distributed knowledge sharing and implementation.

However, the effectiveness of these cross-border structures depends entirely on Member States actually implementing their obligations. As mentioned above, six Member States face infringement procedures for failing to establish functional Digital Services Coordinators, undermining the entire distributed enforcement model.

Strategic litigation and direct action

With regulatory capacity stretched thin, civil society has deployed strategic procedural tools to strengthen enforcement—from collective lawsuits that force judicial clarification of ambiguous rules to direct action that generates political pressure on regulators.

The Irish Council for Civil Liberties filed[107] Ireland’s first class action under the EU Collective Redress Directive against Microsoft over GDPR breaches in its ad tech system, while the Dutch Foundation SOMI launched a collective lawsuit[108] against Meta in Belgium for violating GDPR, DSA, DMA, and consumer protection laws through its “Pay or OK” model. These lawsuits operationalize a critical enforcement procedure: when regulators lack capacity or political will to act, strategic litigation forces judicial interpretation of regulatory ambiguities, creating binding precedents that clarify obligations for all platforms—not just defendants.

When formal procedures prove insufficient, civil society escalates to direct action. Activists protested[109] outside the Berlaymont after the EU’s €2.95 billion[110] Google fine, demanding Competition Commissioner Teresa Ribera move beyond monetary penalties toward structural remedies. Similarly, sustained citizen mobilization in Germany successfully blocked[111] the EU’s “chat control” proposal, demonstrating how public pressure can halt regulatory initiatives through procedural intervention.

These tactics reveal a fundamental procedural challenge: enforcement currently depends on ad-hoc civil society mobilization to compensate for institutional under-capacity. Strategic litigation and direct action work—but unevenly, succeeding where organizations are well-resourced and organized, failing where they aren’t. Sustainable enforcement requires institutionalizing these civil society procedures rather than relying on emergency mobilization, transforming what are reactive interventions into systematic enforcement infrastructure.

Tactics to undermine enforcement

This season, we saw the industry deploying procedural tactics designed to obstruct how enforcement operates in practice. The scale of this effort is growing[112]: the tech and digital industry in the EU is now spending about €151 million annually on lobbying, up from around €113 million in 2023—a 33.6% increase in just two years.

Industry uses public lobbying to demand procedural changes that would weaken enforcement. 46 French and German chief executives wrote to Paris and Berlin demanding “full abolishment[113]” of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive and a moratorium on the implementation and substantial revision of digital regulation such as the Data Act and the AI Act. Apple has been particularly active lobbying to repeal the DMA entirely[114]. While Competition Commissioner Ribera[115] and Commission spokesperson Thomas Regnier[116] publicly rejected these demands, the campaigns create procedural uncertainty that can delay enforcement actions and chill regulatory ambition.

Less visibly, we also saw signals that industry might be attempting to shape enforcement from within institutional structures. Corporate Europe Observatory and LobbyControl filed complaints[117] alleging conflicts of interest in the AI Office’s hiring of consultancies Wavestone and Intellera—both active in the AI market—to help draft AI rules. Similarly, EDRi and 40 civil society organizations raised concerns[118] about the independence of Ireland’s Data Protection Commission following appointments that raised capture questions. These risks are particularly dangerous because they’re less visible than public lobbying campaigns, harder for civil society to counter, and can fundamentally compromise enforcement before any formal proceedings begin. When the institutions designing enforcement procedures or leading investigations have conflicts of interest, the entire architecture becomes suspect—regardless of how well the regulations themselves are written.

Conclusion

European digital policy enforcement is at a crossroads. Europe’s digital rulebook demonstrated real teeth with more big fines, dedicated actions to protect minors, important investigations into LLM training practices, and initial regulatory resistance to AI Act delays.

Yet these enforcement successes occurred against mounting pressures that threaten the entire ecosystem: severe capacity constraints, implementation failures across six countries, increased industry lobbying spending, geopolitical pressure in trade negotiations, and coalition fractures in Parliament that enable regulatory rollbacks.

Most significantly, the Digital Omnibus revealed how quickly enforcement priorities can shift. While regulators advanced concrete enforcement—opening investigations, imposing fines, scrutinizing training data—the Commission simultaneously proposed fundamental changes that could hollow out the very regulations being enforced: redefining GDPR concepts to benefit AI training, delaying AI Act high-risk obligations until 2027-2028 with uncertain acceleration clauses, and allowing providers to self-declare systems as non-high-risk.

Europe spent years building this enforcement infrastructure. Now it’s under attack from multiple directions at once.

Civil society mobilized to stop AI Act delays, and filed collective lawsuits. Nobel laureates defended regulatory timelines. Commission officials publicly pushed back against industry demands for abolishing regulations. But these defensive efforts came at enormous cost—and ultimately proved insufficient. Institutional capacity deficits, political fragmentation, and the sheer scale of corporate influence create structural vulnerabilities that individual enforcement milestones cannot overcome. If it took Nobel laureates and dozens of organizations to temporarily prevent a two-year AI Act delay, only for the Omnibus to ultimately deliver those delays anyway, with even more legal uncertainty, what does that reveal about the balance of power?

What if the Omnibus doesn’t deliver on its promises? Experts[119] highlight the lack of impact assessment, the absence of evidence for claims to such promises, and others[120] draw attention to the simplification agenda being dragged into a false dualism of innovation versus regulation?

What would happen if all this time, effort, and attention were instead devoted to strengthening the enforcement of existing laws, and supporting innovation with capital, talent, and legal harmonisation?

Whether Europe’s digital regulations fundamentally reshape platform power or become words-on-paper depends on choices made now: investing in enforcement capacity through the next Multiannual Financial Framework, strengthening Member State implementation, building public support into enforcement mechanisms systematically, and creating structural reforms like a Digital Enforcement Agency that can withstand geopolitical and industrial headwinds.

Looking forward, the forthcoming Digital Omnibus negotiations will be the immediate test. The previous Sustainability Omnibus took nine months and fractured traditional coalitions. We expect the Digital Omnibus to be no less contentious.

The tech policy enforcement ecosystem has proven it can impose consequences—the question is whether Europe will invest in making that enforcement sustainable, coherent, and resilient enough to match its regulatory ambitions, especially in the face of accelerating technological change.

Endnotes

[1] Centre for Future Generations, ‘Enforcement Tracker’ (2025) https://www.notion.so/Enforcement-Tracker-231ae75aac1481f0b000ce8022b13092 accessed 14 November 2025

[2] European Commission, ‘Simplification and Implementation’ (2025) https://commission.europa.eu/law/law-making-process/better-regulation/simplification-and-implementation_en accessed 14 November 2025

[3] Gkritsi, E. and Haeck, P., ‘Amazon Cloud Outage Fuels Call for Europe to Limit Reliance on US Tech’ Politico (Brussels, 2025) https://www.politico.eu/article/aws-amazon-web-services-outage-europe-limit-reliance-us-tech/ accessed 14 November 2025

[4] European Commission, ‘AI Continent Action Plan’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ai-continent-action-plan accessed 14 November 2025

[5] European Commission, ‘Apply AI Strategy’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/apply-ai accessed 14 November 2025

[6] European Commission, ‘European AI in Science Strategy’ (2025) https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/strategy/strategy-research-and-innovation/our-digital-future/european-ai-science-strategy_en accessed 14 November 2025

[7] Koomen, M. and MacDonald, R., Enforcement in an Age of Accelerated Innovation (CFG, 2024) https://cfg.eu/enforcement-in-an-age-of-accelerated-innovation/#chapter-7 accessed 14 November 2025

[8] Cevik, M.O., ‘Enforcement Spotlight – Spring 2025’ (CFG, 2025) https://cfg.eu/enforcement-spotlight-spring-2025/ accessed 14 November 2025

[9] Csaky, Z., ‘Elections in Poland and Romania: What Do the Results Mean for Europe?’ (Centre for European Reform, 2025) https://www.cer.eu/insights/elections-poland-and-romania-what-do-results-mean-europe accessed 14 November 2025

[10] Datta, A., ‘TikTok announces new measures to combat misinformation ahead of Romanian election’ (2025) https://www.euractiv.com/news/tiktok-announces-new-measures-to-combat-misinformation-ahead-of-romanian-election/ accessed 3 December 2025

[11] TikTok, ‘Protecting the Integrity of TikTok During the Romanian Elections’ (2025) https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-eu/protecting-the-integrity-of-tiktok-during-the-romanian-elections accessed 14 November 2025

[12] Bergmanis-Korāts, G. and others, ‘Impact of the Digital Services Act: A Facebook Case Study’ (NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, 2025) https://stratcomcoe.org/publications/impact-of-the-digital-services-act-a-facebook-case-study/319 accessed 14 November 2025

[13] European Digital Media Observatory, ‘Implementing the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation: An Evaluation of VLOPSE Compliance and Effectiveness (Jan–Jun 2024)’ (2025) https://edmo.eu/publications/implementing-the-eu-code-of-practice-on-disinformation-an-evaluation-of-vlopse-compliance-and-effectiveness-jan-jun-2024/ accessed 14 November 2025

[14] von der Leyen, U., ‘Europe’s Choice: Political Guidelines for the Next European Commission 2024-2029’ (European Commission, 2024) https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/e6cd4328-673c-4e7a-8683-f63ffb2cf648_en?filename=Political%20Guidelines%202024-2029_EN.pdf accessed 14 November 2025

[15] Thomadakis, A., ‘The EU is Walking a Fine Line Between Simplification and Deregulation’ (Centre for European Policy Studies, 2025) https://www.ceps.eu/the-eu-is-walking-the-fine-line-between-simplification-and-deregulation/ accessed 14 November 2025

[16] Cevik, M.O., ‘Enforcement Spotlight – Spring 2025’ (Centre for Future Generations, 2025) https://cfg.eu/enforcement-spotlight-spring-2025/ accessed 14 November 2025

[17] Corlin, P. and Kroet, C., ‘Exclusive: US Pitches Special Role in EU Regulatory Surveillance in Trade Deal’ Euronews (15 July 2025) https://www.euronews.com/business/2025/07/15/exclusive-us-pitches-special-role-in-eu-regulatory-surveillance-in-trade-deal accessed 14 November 2025

[18] Yun Chee, F. and Blenkinsop, P., ‘EU Trade Chief Bound for US, Seeking Deal Fair for Both Sides’ Reuters (30 June 2025) https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/eu-tech-rules-not-included-us-trade-talks-eu-commission-says-2025-06-30/ accessed 14 November 2025

[19] Lima-Strong, C. and Jahangir, R., ‘How US Officials Are Pressuring Europe Over Its Platform Regulations’ Tech Policy Press (2025) https://www.techpolicy.press/how-us-officials-are-pressuring-europe-over-its-platform-regulations/ accessed 14 November 2025

[20] McMenamin, S. and others, ‘Sustainability on the Table: Sustainability Rules in EU/US Trade Talks’ (Matheson, 2025) https://www.matheson.com/insights/detail/sustainability-on-the-table–sustainability-rules-in-eu-us-trade-talks accessed 14 November 2025

[21] Fintech Global, ‘EU Extends Sustainability Reporting Timeline to 2027’ (13 October 2025) https://fintech.global/2025/10/13/eu-extends-sustainability-reporting-timeline-to-2027/ accessed 14 November 2025

[22] Kroet, C., ‘Europe’s Top CEOs Call for Commission to Slow Down on AI Act’ Euronews (3 July 2025) https://www.euronews.com/next/2025/07/03/europes-top-ceos-call-for-commission-to-slow-down-on-ai-act accessed 14 November 2025

[23] Politico Pro, https://pro.politico.eu/news/199865 accessed 14 November 2025

[24] Future Society, ‘Ensuring GPAI Rules Serve the Interests of European Businesses and Citizens’ (2025) https://thefuturesociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/ProtectingGPAIRules.pdf accessed 14 November 2025

[25] EDRi, ‘Open Letter: European Commission Must Champion the AI Act Amidst Simplification Pressure’ (2025) https://edri.org/our-work/open-letter-european-commission-must-champion-the-ai-act-amidst-simplification-pressure/ accessed 14 November 2025

[26] Benoit, M-C., ‘”Stop the Clock”: The Call for a Moratorium on the AI Act Rejected by the European Commission’ Actuia (2025) https://www.actuia.com/en/news/stop-the-clock-the-call-for-a-moratorium-on-the-ai-act-rejected-by-the-european-commission/ accessed 14 November 2025

[27] European Commission, ‘The General-Purpose AI Code of Practice’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/contents-code-gpai accessed 14 November 2025

[28] European Commission, ‘Signatories of Code of Practice’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/contents-code-gpai#ecl-inpage-Signatories-of-the-AI-Pact accessed 14 November 2025

[29] Haeck, P., ‘The EU promised to lead on regulating artificial intelligence. Now it’s hitting pause’, (2025) https://www.politico.eu/article/the-eu-wanted-to-lead-on-regulating-ai-now-its-hitting-pause/ accessed 20 November 2025

[30] Toffaletti, S., ‘Digital Omnibus: A step forward, but Europe still needs its own tech stack’, (2025) https://www.digitalsme.eu/digital-omnibus-a-step-forward-but-europe-still-needs-its-own-tech-stack/ accessed 20 November 2025

[31] Moreau, C., ‘Commission plans sweeping cuts to tech laws to pave the way for AI’, (2025) https://www.euractiv.com/news/commission-plans-sweeping-cuts-to-tech-laws-to-pave-the-way-for-ai/ accessed 20 November 2025

[32] Wyrobek, A. (2025) https://www.linkedin.com/posts/anja-wyrobek_safeguarding-europes-regulatory-leadership-activity-7394066445833248768-KWM3?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAGAu1ysBwidIjfD2tPAKXsHOHX1l5mI7pNA accessed 21 November 2025

[33] Amnesty International, ‘Joint statement: The EU must uphold hard-won protections for digital human rights’, (2025) https://www.amnesty.eu/news/eu-must-uphold-protections-for-digital-human-rights/

[34] Cofone, I., (2025) https://www.linkedin.com/posts/ignaciocofone_how-the-eu-botched-its-attempt-to-regulate-activity-7397281136999235585-wdqV?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAGAu1ysBwidIjfD2tPAKXsHOHX1l5mI7pNA accessed 20 November 2025

[35] Scannell, B. (2025), https://www.linkedin.com/posts/dr-barry-scannell-bbb5aa207_breaking-the-european-commission-just-published-activity-7396913899834609665-RMAq?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAGAu1ysBwidIjfD2tPAKXsHOHX1l5mI7pNA accessed 20 November 2025

[36] Gros, M. and Griera, M., ‘Socialists Cave to Center-Right Demands to Slash EU Green Rules’ Politico (Brussels, 2025) https://www.politico.eu/article/socialists-liberals-epp-eu-green-rules/ accessed 14 November 2025

[37]von der Leyen, U., ‘2025 State of the Union Address’ (European Commission, 2025) https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/ov/speech_25_2053 accessed 14 November 2025

[38] von der Leyen, U., ‘Speech at the Copenhagen Competitiveness Summit’ (European Commission, 2025) https://luxembourg.representation.ec.europa.eu/actualites-et-evenements/actualites/speech-president-von-der-leyen-copenhagen-competitiveness-summit-2025-10-01_en?prefLang=de accessed 14 November 2025

[39] EDRi, ‘Consultation Response to the European Commission’s Call for Evidence on the Digital Omnibus’ (2025) https://edri.org/our-work/consultation-response-to-the-european-commissions-call-for-evidence-on-the-digital-omnibus/ accessed 14 November 2025

[40] Good Lobby, ‘Over 100 Legal Experts Warn Omnibus I Risks Breaching EU Law’ (2025) https://thegoodlobby.eu/over-100-legal-experts-warn-omnibus-i-risks-breaching-eu-law/ accessed 14 November 2025

[41] European Ombudsman, ‘Ombudsman finds maladministration in how Commission prepared urgent legislative proposals’ (2025) https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/press-release/en/215989

[42] Cevik, M.O. and Koomen, M., ‘Enforcement Initiative’ (Centre for Future Generations, 2025) https://cfg.eu/enforcement-initiative/ accessed 14 November 2025

[43] Court of Justice of the European Union, ‘Press Release: The Court of Justice clarifies the scope of the concept of personal data in the context of a transfer of pseudonymised data to third parties’ (2025) https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2025-09/cp250107en.pdf accessed 20 November 2025

[44] Olazábal, I. D., (2025) https://www.linkedin.com/posts/itxaso-dom%C3%ADnguez-de-olaz%C3%A1bal_digitalomnibus-gdpr-eprivacy-activity-7396934200047841281-eGFv?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAGAu1ysBwidIjfD2tPAKXsHOHX1l5mI7pNA accessed 20 November 2025

[45] Noyb, ‘Digital Omnibus: EU Commission wants to wreck core GDPR principles’, (2025) https://noyb.eu/en/digital-omnibus-eu-commission-wants-wreck-core-gdpr-principles accessed 20 November 2025

[46] Domínguez de Olazábal, I., ‘Why Ireland is the Achilles Heel of the EU’s Fightback Against Big Tech’ EUobserver (2025) https://euobserver.com/digital/arfd2322c4 accessed 14 November 2025

[47] Irish Data Protection Commission, ‘Data Protection Commission Announces Commencement of Inquiry into X Internet Unlimited Company (XIUC)’ (2025) https://www.dataprotection.ie/en/news-media/latest-news/data-protection-commission-announces-commencement-inquiry-x-internet-unlimited-company-xiuc accessed 14 November 2025

[48] noyb, ‘noyb Sends Meta “Cease and Desist” Letter Over AI Training. European Class Action as Potential Next Step’ (2025) https://noyb.eu/en/noyb-sends-meta-cease-and-desist-letter-over-ai-training-european-class-action-potential-next-step accessed 14 November 2025

[49] Irish Data Protection Commission, ‘DPC Statement on Meta AI’ (2025) https://www.dataprotection.ie/en/news-media/latest-news/dpc-statement-meta-ai accessed 14 November 2025

[50] MLex, ‘Meta Cleared to Start AI Training in Germany After Court Rejects Injunction Bid’ (2025) https://content.mlex.com/#/content/1656687/meta-cleared-to-start-ai-training-in-germany-after-court-rejects-injunction-bid accessed 14 November 2025

[51] Noyb, ‘Digital Omnibus: EU Commission wants to wreck core GDPR principles’, (2025) https://noyb.eu/en/digital-omnibus-eu-commission-wants-wreck-core-gdpr-principles accessed 20 November 2025

[52] Ada Lovelace, ‘Our response to the official text of the EU Digital Omnibus Regulation Proposal’ (2025) https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/news/our-response-to-the-eu-digital-omnibus-regulation-proposal/ accessed 20 November 2025

[53] European Commission, ‘AI Continent Action Plan’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ai-continent-action-plan accessed 14 November 2025

[54] European Commission, ‘Apply AI Strategy’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/apply-ai accessed 14 November 2025

[55] European Commission, ‘European AI in Science Strategy’ (2025) https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/strategy/strategy-research-and-innovation/our-digital-future/european-ai-science-strategy_en accessed 14 November 2025

[56] European Commission, ‘Commission Launches AI Act Service Desk and Single Information Platform to Support AI Act Implementation’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/commission-launches-ai-act-service-desk-and-single-information-platform-support-ai-act accessed 14 November 2025

[57] Government of the Netherlands, ‘Fundamental Rights and Algorithms Impact Assessment (FRAIA)’ (2025) https://www.government.nl/documents/reports/2021/07/31/impact-assessment-fundamental-rights-and-algorithms accessed 14 November 2025

[58] Haeck, P., ‘The EU promised to lead on regulating artificial intelligence. Now it’s hitting pause’, (2025) https://www.politico.eu/article/the-eu-wanted-to-lead-on-regulating-ai-now-its-hitting-pause/ accessed 20 November 2025

[59] Scannell, B., (2025) https://www.linkedin.com/posts/dr-barry-scannell-bbb5aa207_breaking-the-european-commission-just-published-activity-7396913899834609665-RMAq?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAGAu1ysBwidIjfD2tPAKXsHOHX1l5mI7pNA accessed 20 November 2025

[60] Bertuzzi, L., (2025) https://www.linkedin.com/posts/luca-bertuzzi-186729130_breaking-the-european-commission-has-just-activity-7396891962902999042-7ekI?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAGAu1ysBwidIjfD2tPAKXsHOHX1l5mI7pNA accessed 20 November 2025

[61] European Commission, ‘Digital Omnibus Regulation Proposal’, (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/digital-omnibus-regulation-proposal accessed 20 November 2025

[62] Moreau, C., ‘Commission plans sweeping cuts to tech laws to pave the way for AI’, (2025) https://www.euractiv.com/news/commission-plans-sweeping-cuts-to-tech-laws-to-pave-the-way-for-ai/ accessed 20 November 2025

[63] EDRI, ‘Press Release: Commission’s Digital Omnibus is a major rollback of EU digital protections’ (2025) https://edri.org/our-work/commissions-digital-omnibus-is-a-major-rollback-of-eu-digital-protections/

[64] TIC Council, (2025) https://www.linkedin.com/posts/tic-council_omnibus-ai-aiact-activity-7396911422171156481-j8X9?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAGAu1ysBwidIjfD2tPAKXsHOHX1l5mI7pNA accessed 20 November 2025

[65] Cevik, M.O., Koomen, M. and Mahieu, V., ‘Emerging Tech, Emerging Mental Health Risks’ (Centre for Future Generations, 2025) https://cfg.eu/emerging-tech-emerging-mental-health-risks/ accessed 14 November 2025

[66] CFG ‘Enforcement Tracker (2025) https://www.notion.so/Enforcement-Tracker-231ae75aac1481f0b000ce8022b13092 accessed 14 November 2025

[67] European Commission, ‘Commission Opens Investigations to Safeguard Minors from Pornographic Content Under the Digital Services Act’ (2025) https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_1339 accessed 14 November 2025

[68] Politico Pro (2025) https://pro.politico.eu/news/198972 accessed 14 November 2025

[69] Politico Pro, [Article Title Unknown] (2025) https://pro.politico.eu/news/199575 accessed 14 November 2025

[70] European Commission, ‘Commission Publishes Guidelines on the Protection of Minors’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/commission-publishes-guidelines-protection-minors accessed 14 November 2025

[71] European Commission, ‘The EU Approach to Age Verification’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/eu-age-verification accessed 14 November 2025

[72] European Commission, ‘Commission Releases Enhanced Second Version of the Age-Verification Blueprint’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/commission-releases-enhanced-second-version-age-verification-blueprint accessed 14 November 2025

[73]Centre for Future Generations, ‘Response to the Public Consultation on the Digital Fairness Act’ (2025) https://cfg.eu/response-digital-fairness-act/ accessed 14 November 2025

[74] European Commission, ‘DMA Annual Reports’ (2025) https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/about-dma/dma-annual-reports_en accessed 14 November 2025

[75]European Commission, ‘Commission Finds Apple and Meta in Breach of the Digital Markets Act’ (2025) https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_1085 accessed 14 November 2025

[76] Apple, ‘Updates for Apps in the European Union’ (2025) https://developer.apple.com/news/?id=awedznci accessed 14 November 2025

[77] Politico Pro, (2025) https://pro.politico.eu/news/201035 accessed 14 November 2025

[78] European Commission, ‘Commission Gathers Views on How the DMA Can Support Fair and Contestable Digital Markets and AI Sector’ (2025) https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/commission-gathers-views-how-dma-can-support-fair-and-contestable-digital-markets-and-ai-sector-2025-08-27_en accessed 14 November 2025

[79]Cevik, M.O., ‘Enforcement Spotlight – Spring 2025’ (2025) https://cfg.eu/enforcement-spotlight-spring-2025/ accessed 14 November 2025

[80] European Personnel Selection Office, ‘Digital Services Act (DSA) Specialist Officers and Assistants (6 Different Profiles)’ (2025) https://eu-careers.europa.eu/en/job-opportunities/digital-services-act-dsa-specialist-officers-and-assistants-6-different-profiles accessed 14 November 2025

[81] MLex, ‘Grossly Understaffed: EU Competition Enforcers Must Prioritize, Guersent Says’ (2025) https://content.mlex.com/#/content/1644817/grossly-understaffed-eu-competition-enforcers-must-prioritize-guersent-says accessed 14 November 2025

[82]Contexte, ‘Letter to Incoming Commissioner on Openwashing’ (April 2025) https://www.contexte.com/medias/pdf/medias-documents/2025/4/letter-to-incoming-commissioner-on-openwashing.pdf accessed 14 November 2025

[83] European Commission, ‘Commission Decides to Refer Czechia, Spain, Cyprus, Poland and Portugal to the Court of Justice of the European Union Due to Lack of Effective Implementation of the Digital Services Act’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/commission-decides-refer-czechia-spain-cyprus-poland-and-portugal-court-justice-european-union-due accessed 14 November 2025

[84] Civil Liberties Union for Europe, ‘Monitoring the Implementation of the Digital Services Act: The Independence of Digital Services Coordinators’ (2025) https://dq4n3btxmr8c9.cloudfront.net/files/0ol1bo/Liberties_DSA_Monitoring_Febr2025.pdf accessed 14 November 2025

[85] European Commission, ‘Commission Seeks Experts for AI Scientific Panel’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/commission-seeks-experts-ai-scientific-panel accessed 14 November 2025

[86] European Commission, ‘Delegated Act on Data Access Under the Digital Services Act (DSA)’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/delegated-act-data-access-under-digital-services-act-dsa accessed 14 November 2025

[87] Bundesnetzagentur, ‘Bundesnetzagentur as Digital Services Coordinator, Certifies More Trusted Flaggers’ (2025) https://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2025/20250602_TrustedFlagger.html accessed 14 November 2025

[88] Coimisiún na Meán, ‘The Central Bank of Ireland Awarded Trusted Flagger Status’ (2025) https://www.cnam.ie/the-central-bank-of-ireland-awarded-trusted-flagger-status/ accessed 14 November 2025

[89] Corporate Europe Observatory, ‘Lobby Watchdogs File Complaint Against AI Office Over Conflict of Interest’ (2025) https://corporateeurope.org/en/2025/06/lobby-watchdogs-file-complaint-against-ai-office-over-conflict-interest accessed 14 November 2025

[90] EDRi, ‘Open Letter: The EU Must Safeguard the Independence of Data Protection Authorities’ (2025) https://edri.org/our-work/open-letter-the-eu-must-safeguard-the-independence-of-data-protection-authorities/ accessed 14 November 2025

[91] Article 19, ‘The Future of Democracy: Speech, Thought, Sovereignty, and Power in the Age of Platforms and AI’ (2025) https://www.article19.org/resources/the-future-of-democracy-speech-thought-sovereignty-and-power-in-the-age-of-platforms-and-ai/ accessed 14 November 2025

[92] Bertuzzi, L., ‘Breaking: ChatGPT Could Soon Become a Regulated…’ [LinkedIn post] (2025) https://www.linkedin.com/posts/luca-bertuzzi-186729130_breaking-chatgpt-could-soon-become-a-regulated-activity-7386489072380178433-_f0I accessed 14 November 2025

[93] Gkritsi, E., ‘The EU Can’t Figure Out What to Do About ChatGPT’ Politico (Brussels, 2025) https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-chatgpt-ai-digital-law-tech-openai-regulations-legal/ accessed 14 November 2025

[94] European Commission, ‘Commission Opens Investigations to Safeguard Minors from Pornographic Content Under the Digital Services Act’ (2025) https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_1339 accessed 14 November 2025

[95]European Commission, ‘Commission Finds Apple and Meta in Breach of the Digital Markets Act’ (2025) https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_1085 accessed 14 November 2025

[96] Henning, M., ‘The Two-Fold Case for a New EU Tech Enforcement Agency’ Euractiv (2025) https://www.euractiv.com/news/the-two-fold-case-for-a-new-eu-tech-enforcement-agency/ accessed 14 November 2025

[97] Koomen, M. and MacDonald, R., ‘Enforcement in an Age of Accelerated Innovation’ (Centre for Future Generations, 2024) https://cfg.eu/enforcement-in-an-age-of-accelerated-innovation/ accessed 14 November 2025

[98] Wiewiórowski, W., ‘Towards Digital Clearinghouse 2.0: Championing a Consistent Supervisory Approach for the Digital Economy’ (European Data Protection Supervisor, 2025) https://www.edps.europa.eu/press-publications/press-news/blog/towards-digital-clearinghouse-20-championing-consistent-approach-digital-economy_en accessed 14 November 2025

[99]European Commission, ‘DMA Stakeholders Workshops’ (2025) https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/events/workshops_en accessed 14 November 2025

[100] European Commission, ‘European Commission Launches Workshops to Explore Voluntary Codes of Conduct for Online Advertising’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/european-commission-launches-workshops-explore-voluntary-codes-conduct-online-advertising accessed 14 November 2025

[101] European Commission, ‘European Commission Hosts Expert Consultation Workshop on Draft Guidelines on Protection of Minors Under the DSA’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/european-commission-hosts-expert-consultation-workshop-draft-guidelines-protection-minors-under-dsa accessed 14 November 2025

[102]Bergmanis-Korāts, G. and others, ‘Impact of the Digital Services Act: A Facebook Case Study’ (NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, 2025) https://stratcomcoe.org/publications/impact-of-the-digital-services-act-a-facebook-case-study/319 accessed 14 November 2025

[103] European Digital Media Observatory, ‘Implementing the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation: An Evaluation of VLOPSE Compliance and Effectiveness (Jan–Jun 2024)’ (2025) https://edmo.eu/publications/implementing-the-eu-code-of-practice-on-disinformation-an-evaluation-of-vlopse-compliance-and-effectiveness-jan-jun-2024/ accessed 14 November 2025

[104] Cevik, M.O. and Koomen, M., ‘Enforcement Initiative’ (Centre for Future Generations, 2025) https://cfg.eu/enforcement-initiative/ accessed 14 November 2025

[105]Appeals Centre Europe, ‘New EU Network Helps Users to Challenge Online Platforms’ Decisions’ (2025) https://www.appealscentre.eu/eu-digital-services-act-ods-network-launch/ accessed 14 November 2025

[106] European Commission, ‘The European Board for Digital Services Launches a Coordinated Action to Reinforce the Protection of Minors as Regards Pornographic Platforms’ (2025) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/european-board-digital-services-launches-coordinated-action-reinforce-protection-minors-regards accessed 14 November 2025

[107] Irish Council for Civil Liberties, ‘Microsoft’s Vast Advertising Business is Target of ICCL Enforce Application for Class Action Launch Under EU Data Law’ (2025) https://www.iccl.ie/digital-data/iccl-initiates-irelands-first-ever-class-action-lawsuit-targeting-microsofts-european-advertising-system/ accessed 14 November 2025

[108] MLex, ‘Meta Platforms Faces Class Action by Dutch Foundation Over Pay or Consent Model’ (2025) https://content.mlex.com/#/content/1664037/meta-platforms-faces-class-action-by-dutch-foundation-over-pay-or-consent-model accessed 14 November 2025

[109] Datta, A., ‘Protesters Outside Berlaymont Urge EU to Break Up Google’ Euractiv (2025) https://www.euractiv.com/news/protesters-outside-berlaymont-urge-eu-to-break-up-google/ accessed 14 November 2025

[110]European Commission, ‘Commission Fines Google €2.95 Billion Over Abusive Practices in Online Advertising Technology’ (2025) https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_1992 accessed 14 November 2025

[111] Breyer, P., ‘Citizen Protest Halts Chat Control; Breyer Celebrates Major Victory for Digital Privacy’ (2025) https://www.patrick-breyer.de/en/citizen-protest-halts-chat-control-breyer-celebrates-major-victory-for-digital-privacy/ accessed 14 November 2025

[112] Corporate Europe Observatory, ‘Revealed: Tech Industry Now Spending Record €151 Million on Lobbying the EU’ (2025) https://corporateeurope.org/en/2025/10/revealed-tech-industry-now-spending-record-eu151-million-lobbying-eu accessed 14 November 2025

[113]Baddache, F., ‘CSDDD Under Siege: Why Business Divides on Regulation’ KSAPA (2025) https://ksapa.org/csddd-under-siege-why-business-divides-on-regulation/ accessed 14 November 2025

[114]Regnier, T., ‘We Have Received and We Are Not Surprised…’ [LinkedIn post] (2025) https://www.linkedin.com/posts/thomas-regnier-24a05810b_we-have-received-and-we-are-not-surprised-activity-7376997375997018112-fsi_ accessed 14 November 2025

[115] Ribera, T., ‘I Appreciate the Commitment to a More Competitive…’ [LinkedIn post] (2025) https://www.linkedin.com/posts/teresa-ribera-42a08b340_i-appreciate-the-commitment-to-a-more-competitive-activity-7382472406256381952-P8im/ accessed 14 November 2025

[116] Regnier, T., ‘We Have Received and We Are Not Surprised…’ [LinkedIn post] (2025) https://www.linkedin.com/posts/thomas-regnier-24a05810b_we-have-received-and-we-are-not-surprised-activity-7376997375997018112-fsi_ accessed 14 November 2025

[117] Corporate Europe Observatory, ‘Lobby Watchdogs File Complaint Against AI Office Over Conflict of Interest’ (2025) https://corporateeurope.org/en/2025/06/lobby-watchdogs-file-complaint-against-ai-office-over-conflict-interest accessed 14 November 2025