Towards a European BioPower

Europe is facing huge geopolitical challenges, from economic pressures exerted by the US and growing assertiveness by China, to regional conflicts exemplified by the crisis in Ukraine. Yet within these challenges lies a remarkable opportunity European policymakers must seize: the concept of “European BioPower” as a strategic dual use pathway for biotechnologies (e.g. advanced biomaterials, deployable biomanufacturing systems, AI-driven biological intelligence platforms). “BioPower” means the establishment of biotechnology as a core pillar of one geopolitical posture through the deliberate alignment of policy, investment, and innovation.

By committing to regulatory clarity, public-private innovation pipelines, and integrated bio-industrial policy, the EU Europe has the opportunity to transform its latent strengths in bioengineering and artificial intelligence into levers of economic power and geopolitical resilience. Europe can operationalise its BioPower by prioritising innovation in dual-use biotechnology and turning cutting-edge biotech capabilities into tools for resilience, competitiveness, and defence. With the European Defence White Paper explicitly recognising biotechnology as a “foundational technology” critical to both ”economic growth, and military pre-eminence”, it is clear that Europe recognises the need to seize this pivotal chance. It will take the implementation of policy interventions that bridge research-industry gaps, support emerging ventures, and foster cross-border collaboration. Only with a coordinated, bloc-wide approach can Europe transform its fragmented biotechnology landscape into a cohesive ecosystem that rivals global competitors.

The need for European BioPower

In an era of intensifying geopolitical tensions, the traditional contours of national security and defence are rapidly evolving beyond conventional military capabilities. The boundaries between national security and defence are blurring, because the threats presented by technologies are also blurring. Recognising this shift, the European Union has identified biotechnology among the ten critical technologies essential for ensuring economic security.

Recent global events have transformed theoretical security vulnerabilities into immediate strategic imperatives. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has demonstrated the concrete consequences of technological dependence, as disruptions to energy, food, and medical supply chains exposed critical vulnerabilities in Europe’s security architecture and industrial autonomy. Most importantly, as outlined in the recent White Paper for European Defence, this conflict revealed that future resilience will depend on more than traditional defense capabilities. Increasingly, technological sovereignty in strategically vital sectors will determine security outcomes. The economic case for European leadership already exists. Between 2008 and 2018, Europe’s biotechnology industry grew more than twice as fast as the overall economy. Biotechnology directly contributes €38.11 billion to the EU’s GDP (approximately 1.58% of the European industrial sector) and, when indirect and induced effects are accounted for, this reaches €75.16 billion – roughly half the GDP contribution of the European R&D sector as a whole.

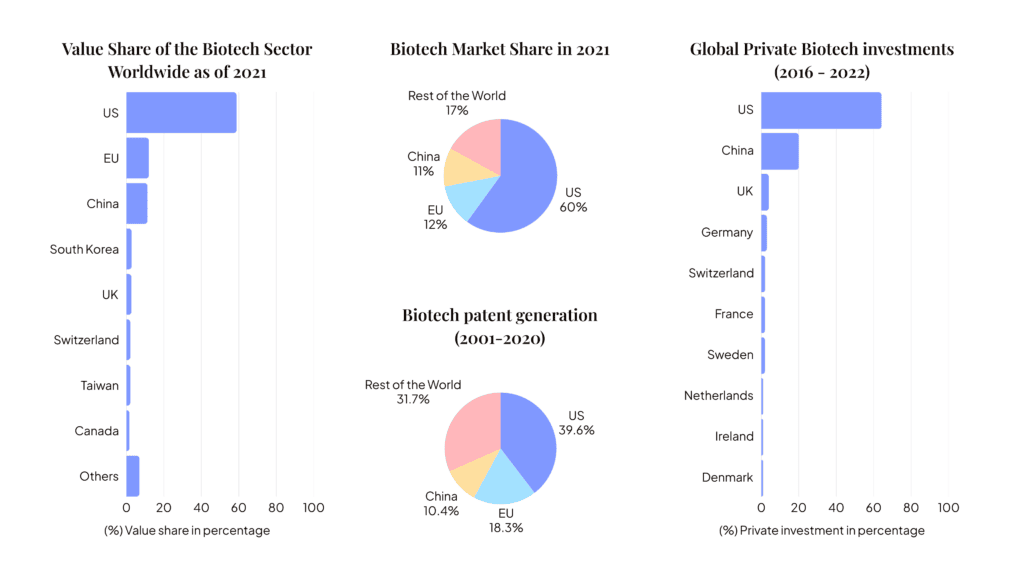

Despite this foundation, Europe’s global competitive position is rapidly eroding. The global biotechnology market reached €720 billion in 2021, with the EU contributing only 12% of this value, while the United States commands 60% and China’s share has grown to 11% (Figure 1). This gap is evident in innovation outputs: the United States dominates biotechnology patent generation with 39.6% of global biotech patents, while Europe’s share has declined to just 18.3% and China has raised up to 10.4% (Figure 1). In capital markets, the disparity is even more pronounced. From 2016 to 2022 the US dominates with 64.16% of global investments reflecting its mature biotech ecosystem built upon prestigious research universities and established venture capital networks (Figure 1). China has emerged as the second player with 20.23% of private investments demonstrating its strategic national push to become a biotech powerhouse. European Union member states collectively account for just 9.36% of global biotech investments, highlighting Europe’s fragmented biotech landscape and suggesting potential challenges in scaling companies across national borders despite the region’s strong scientific foundation. This significant investment gap explains why European biotech companies often struggle to reach the commercial scale of their American counterparts, frequently becoming acquisition targets for US pharmaceutical giants rather than growing into global leaders themselves.

These indicators reflect a systematic inability to translate Europe’s strong scientific foundation into market leadership, creating both economic and strategic vulnerabilities as global competitors pull ahead. The European Commission’s 2024 Communication on Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing was an initial response to this challenge. Building on this foundation, the White Paper for European Defence took a crucial step by explicitly recognizing the “European paradox” – where scientific excellence consistently fails to generate commercial success or strategic military capabilities.

This recognition by the Commission of biotechnology’s dual-use potential follows both the United States and China, who have already established comprehensive frameworks that capitalise on biotechnology’s capabilities to advance their economic and defense interests. Historically, the United States, through DARPA’s Biological Technologies Office, has invested billions in synthetic biology, advanced biomaterials, and biomedical countermeasures that serve both defense priorities and civilian markets. Similarly, China has deliberately positioned biotechnology at the heart of its “Military-Civil Fusion” strategy, creating seamless pathways for innovations in genomics and biomanufacturing to flow between commercial enterprises and defense establishments.

The White Paper for European Defence finally acknowledged the strategic importance of investing in dual-use technologies and identified Quantum and Artificial Intelligence (AI) as major priorities. However, Wwhile biotechnology was mentioned in the paper, it was missing a concrete action point to utilise its strategic potential. CFG believes it should be elevated as a third pillar of this new dual-use strategy. Focusing on biotechnology would capitalise on Europe’s established scientific and industrial leadership in this field, but also accelerate BioPower development, bypassing domains where Europe must first build competitive baseline capacity, such as AI and Quantum.

This requires a fundamental shift in our approach by creating productive interfaces between civilian research and defense innovation in biotechnology. Currently, Europe operates with largely siloed research ecosystems for civilian biotechnology and defence applications. Unlike the U.S. or China, the EU lacks a coordinated framework specifically designed to facilitate the transition of biotechnology innovations between these sectors. The European Defence Agency and The Directorate-General for Defence Industry and Space (DG DEFIS) operate separate platforms from civilian research institutions, creating redundancies and inefficiencies in knowledge transfer.

For example, as a coordination approach, the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB) has laid important groundwork — in aligning defence planning and funding research for military applications. However the EDTIB and the recently proposed SAFE regulation don’t explicitly draw out the potential role for biotechnologies.

The existing structures, while supporting individual streams of research excellence, fail to capitalise on the inherently dual-use nature of biotechnology innovations, leaving significant untapped potential for both security applications and commercial development. However, the Commission proposal to expand the scope of the Strategic Technologies for Europe Platform (STEP) to include defence, which does isolate biotechnology as a strategic sector, can go some way in supporting the development of a European Biopower. Breaking down these divisions is an approach that directly aligns with the European vision for “breakthrough technologies“ that support both defense readiness and industrial competitiveness. As Europe embarks on “a once-in-a-generation surge in European defence investment“, biotechnology represents an ideal domain for maximising returns.

Leveraging biotechnology for dual use innovation

Europe currently maintains separate innovation streams for civilian and defense technologies, a division that reflects differing governance structures and policy objectives across the EU ecosystem. While this separation serves essential purposes in many domains, in biotechnology this divide creates significant inefficiencies and missed opportunities. The inherent dual-use nature of biotech innovations means that siloed development pathways lead to duplicated efforts, fragmented funding, and ultimately, a competitive disadvantage in the global biotech landscape – outweighing the risk-reduction benefits of our current siloed model. China’s Military-Civil Fusion strategy reveals a calculated approach to achieving military dominance by 2049. By eliminating barriers between civilian research and defense sectors, China creates a seamless pathway for acquiring global intellectual property and technological innovations.

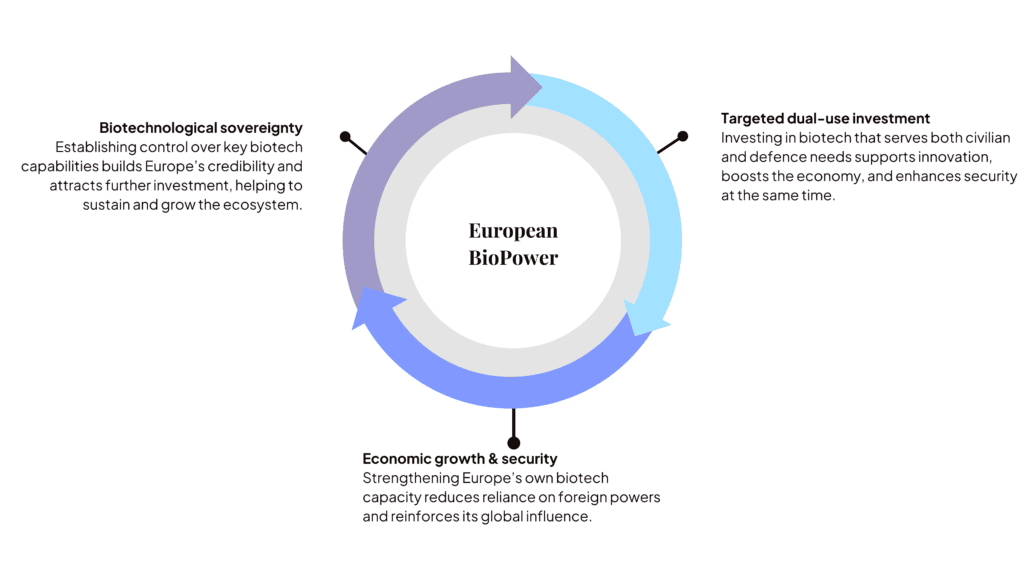

As such, a coherent agenda for establishing European BioPower would transcend our traditional boundaries, identifying and systematically supporting specific biotechnologies with dual-use potential. This integrated approach would ensure that technologies are simultaneously developed for both defense applications and civilian markets, creating a virtuous cycle of innovation that strengthens Europe’s strategic autonomy while enhancing its industrial competitiveness. Critically, defense sector involvement would significantly de-risk biotech investments, making the entire ecosystem more attractive for private capital.

The Draghi report and the EU Competitiveness Compass highlighted that Europe’s future security and prosperity depend on technological autonomy in critical domains, including biotechnology. The strategic thinking in these documents provide the foundation for a number of current and upcoming EU initiatives that have the potential, if properly aligned, to drive a comprehensive European BioPower agenda. These include, but are not limited to:

- The Bioeconomy Strategy and Life Sciences Strategy

- The Critical Raw Materials Act

- The Start-up and Scale-up Strategy

- The Clean Industrial Deal

- The European Savings and Investment Union

- The EU Biotech Act

The recent draft ITRE report on the future of EU biotechnology and biomanufacturing has gone further and recommended streamlining and harmonising upcoming and current initiatives relating to biotechnology and biomanufacturing. This is a critical point. Piecemeal initiatives will not deliver the coordinated step-change needed to bring a European BioPower into being. A holistic biotech ecosystem could foster biodefense investment from a necessary cost into a powerful engine of innovation that enhances both security and prosperity across the European Union.

Examples of strategic biotechnology sectors

Although details concerning these specific sectors require further elaboration by technical experts, examples of technologies that can contribute to EU BioPower span a number of sectors: from advancements in biomanufacturing (materials and decontamination) and robotics in biotechnology, through deployable biotech products for medical use, to biointelligence.

- Biomaterials for defense: Developing advanced bio-based materials that provide superior protection, infrastructure resilience, and sustainability benefits for both military applications and civilian infrastructure. Biomanufactured textiles could protect soldiers with “spider silk” armor that is both lighter and up to three times tougher than Kevlar. Similarly, research into self-repairing construction materials (e.g., biologically enhanced concrete that autonomously addresses structural degradation) offers potential to extend the lifespan of critical infrastructure while reducing maintenance burdens.

- Bioremediation: Utilizing biological systems for environmental decontamination after conflicts or accidents, with parallel applications in civilian environmental restoration. This technology has high potential to clean up environmental contamination post-conflict or after accidents enhancing resilience. Civilian applications include depollution of soils, rivers and environment and overall contribution of Europe for sustainable ecology.

- Robotics in Biotechnologies: Advancing automated systems for biological research and production, increasing both security and industrial productivity. One particular innovation to highlight is Cloud Labs. These have been tagged as “Technologies to watch in 2025” by the journal Nature. Cloud labs are remote facilities that have equipment to which researchers can outsource their experimental workflow. The creation of a European Cloud Lab Network with both defense and civilian access protocols, similar to the model used for national supercomputing resources, might strengthen a nation’s overall biotechnology capabilities, and ensure a distributed and secure biodefense research. Unfortunately no cloud labs infrastructure exists in Europe and the US is currently leading the show in this innovation space.

- Biotech products for medical use: Creating field-deployable biomanufacturing capabilities for critical therapeutics, which serve both battlefield medicine and disaster response scenarios. Innovations such as synthetic, shelf-stable blood substitutes could improve trauma care in hostile environments. This field is capital-intensive and dominated by U.S. players like KaloCyte or HemoGenyx. There are startups and research-driven initiatives in Europe working on innovative substitutes for human blood or portable blood-production systems but several of these initiatives are lacking the necessary funds to scale up. Another area of interest is biomanufacturing and how to develop compact bioreactor systems capable of producing vital therapeutics (e.g., haemorrhage control agents, antibiotics, tissues) on-site would ensure rapid access to life-saving treatments. These solutions, among others, have parallel applications in disaster relief and remote healthcare, bridging critical gaps in global medical supply chains.

- BioIntell: Leveraging bioinformatics and AI to predict and prevent biological threats, enhancing both military intelligence and public health biosurveillance. This complements TeChBioT‘s AI-driven approach, offering strategic advantages. Civilian applications include biosurveillance for emerging infectious disease and unexpected biothreats. It could work as a complement to the current EU Health Security Strategy.

How to implement a European BioPower strategy

To bring this vision to life, Europe must align biotechnology defense with broader EU strategic goals. This requires a coordinated approach that encompasses various policy mechanisms. including the European Defense Fund, the EU Biotech Act, the Critical Raw Materials Act, and the Strategic Technologies for Europe Platform (STEP). There is a clear window of opportunity to transform biotech defense into an economic powerhouse by creating a self-sustaining ecosystem where defense innovation fuels civilian prosperity.

Specific policy interventions could include:

- Bridging Research and Industry: The European biotech sector is characterized by a variety of startups operating independently, often with limited access to shared resources and collaborative networks. This fragmentation may lead to inefficiencies and challenges in scaling operations. A network of cloud Labs and EU BioFoundries would democratize advanced tools and enable SMEs to prototype innovations at scale. By establishing shared infrastructure across member states, Europe could transform its fragmented biotech landscape into a cohesive ecosystem that builds sovereign capabilities in critical biotechnologies. This would be essential for establishing Europe as a competitive biopower on the global stage.

- Strategic investments: Increase funding through defense and innovation mechanisms and support venture capital for biotech companies, leveraging additional investments (i.e., Strengthening Europe’s Security). Also a simplified process for a joint procurement might support the demand and ensure innovation is accessible to all European member states. A particularly powerful approach would be equipping the European Innovation Council with novel funding mechanisms specifically designed to support a sectoral investment strategy for European biopower. Such institutional backing would signal market credibility and effectively attract venture capital funding to strategic technologies with dual-use applications.

- Encourage collaboration: encouragement of cross-border partnerships among member states, support for startups and SMEs developing dual-use biotechnologies, and investment in state-of-the-art biomanufacturing facilities. These efforts should be coordinated through specialised regional hubs that can foster both competition and collaboration in niche biotech defense fields.

- Modernise public procurement: public procurement is an essential tool to create and diffuse dual-use innovation, and it needs an upgrade across rules, talent, tech, and culture. Not coincidentally, in her political guidelines for the next European Commission, then-president-elect Ursula von der Leyen, highlighted that: “a 1% efficiency gain in public procurement could save EUR 20 billion a year”. Current procurement processes are unfit to shape the biotech market and help institutions and businesses acquire knowledge, skills, and products speedily. Procurement must become a strategic tool rather than just an administrative process. Joint procurement initiatives at the EU level would generate the consistent, large-scale demand necessary to incentivise private investment and shape the market. Building on successful precedents from the health sector, Advanced Purchase Agreements for specific biotechnologies could establish reserved capacity, similar to mechanisms used for vaccines and PPE stockpiles, providing the market certainty that companies need to make long-term investments.

The creation of European biopower offers multiple strategic benefits: geopolitical autonomy through reduced reliance on foreign biotech capabilities; economic competitiveness driven by defense innovation in high-value sectors; and ethical leadership in establishing global standards for responsible biotechnology use. This approach transforms biotech defense from a cost center into an economic engine, creating a self-sustaining ecosystem where defense innovation fuels civilian prosperity (Figure 2).

It is clear that in the current geopolitical environment, where technological capabilities increasingly determine national power, Europe cannot afford to lag behind in biotechnology. By strategically investing in European biopower as a pillar of the European Defense Union, the EU can simultaneously strengthen its security posture, enhance its industrial competitiveness, and establish leadership in a domain that will shape the future of global power dynamics.