Introducing the Emerging biotechnology atlas

A policymaker’s guide to the biotech revolution

The Emerging biotechnology atlas is a living reference guide that maps and untangles a selection of rapidly-evolving biotechnologies. This Atlas provides a considered contribution to a debate about emerging technologies that too often swings between blind techno‑optimism and paralysing fear. It looks to contribute to the fundamental literacy needed for informed engagement with biotechnology’s evolving landscape. In a field where expertise is siloed and jargon abounds, we aim for clarity without oversimplification, concern without alarmism.

Biotechnology already reaches far beyond research labs, reshaping food systems, healthcare, agriculture, and climate‑industrial strategies [1]. To craft policies that fuel innovation and contribute to society, decision-makers must have a degree of fluency in the language of biotechnology and understanding of how it converges with other technological advancements. Our theory of change is simple: navigate the latest scientific evidence and translate it into the current governance approaches of the EU. By doing this, we empower policymakers to design responsible technology governance that supports progress, with the aim that biotechnology is developed as a force that strengthens our democratic, economic and social systems.

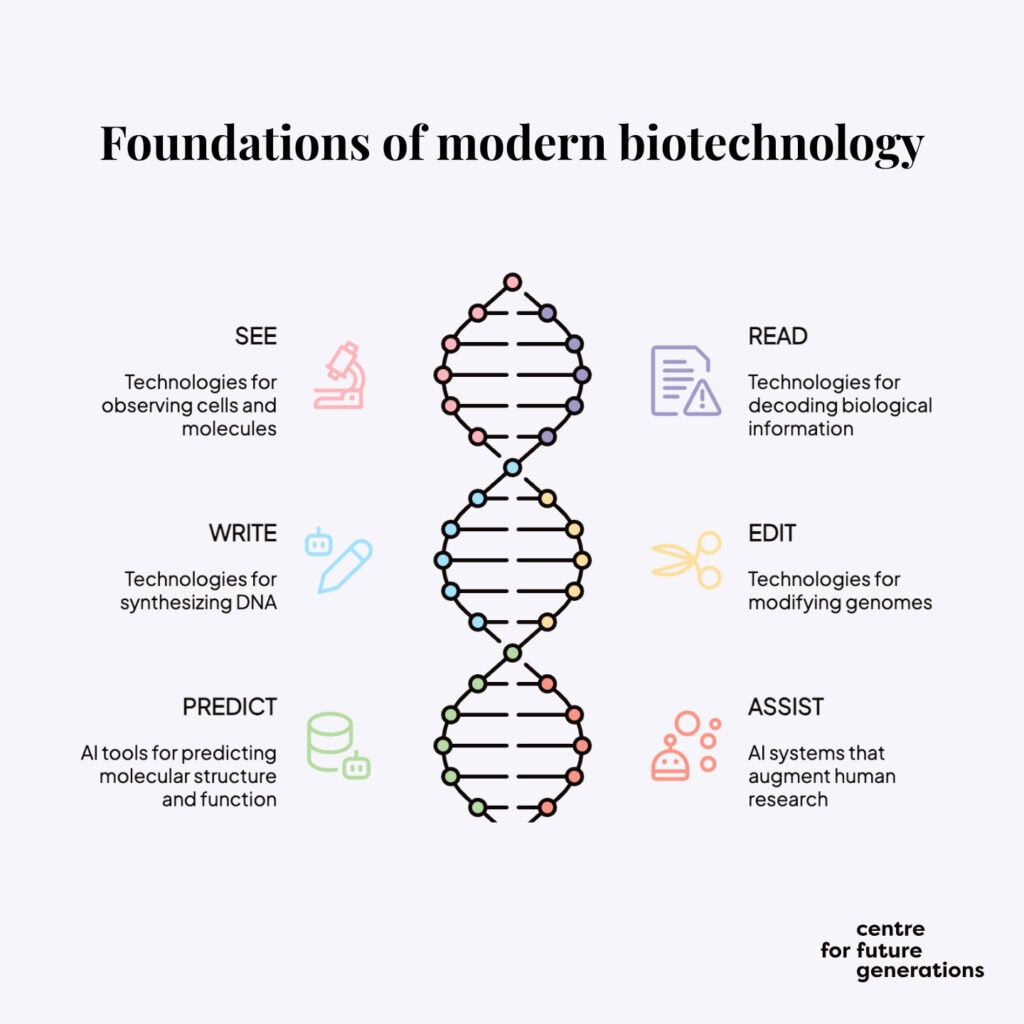

We break down modern biotechnology into six pillars:

- SEE: Technologies that enable the observation of cells and molecules

- READ: Technologies that decode complex biological information into readable data

- WRITE: DNA synthesis technologies that enable us to manufacture genetic material

- EDIT: Gene editing technologies that allow precise modifications to existing genomes

- PREDICT: AI-driven biological tools that craft the structure and function of molecules

- ASSIST: Large language models and agentic AI systems that augment human researchers

This article will give a brief overview of all these pillars, while our Atlas will deeply dive from “write” to “assist”. There we will explain the technology’s main concepts, current capabilities, and how it is regulated at the European level. As the technology evolves rapidly, mapping the regulatory landscape gives some insight into where safety standards and regulatory expertise may struggle to keep up. In practice, these technologies operate in a complex governance web – meaning countries, industry and international organisations sometimes perform governance roles beyond those of the European Union. This is an important caveat and a dimension we hope to explore further in updates to the atlas.

Like the science it traces, our atlas should be seen as a living organism: evolving, adapting, and growing. When CRISPR‑Cas9 gives way to a new gene editing tool or AlphaFold’s models are eclipsed, these pages will reflect this shift. Continuous horizon scanning will keep the science current and dissect emerging policy challenges, in Europe and worldwide. This emerging biotech atlas offers a common reference point amid accelerating change for policymakers and society.

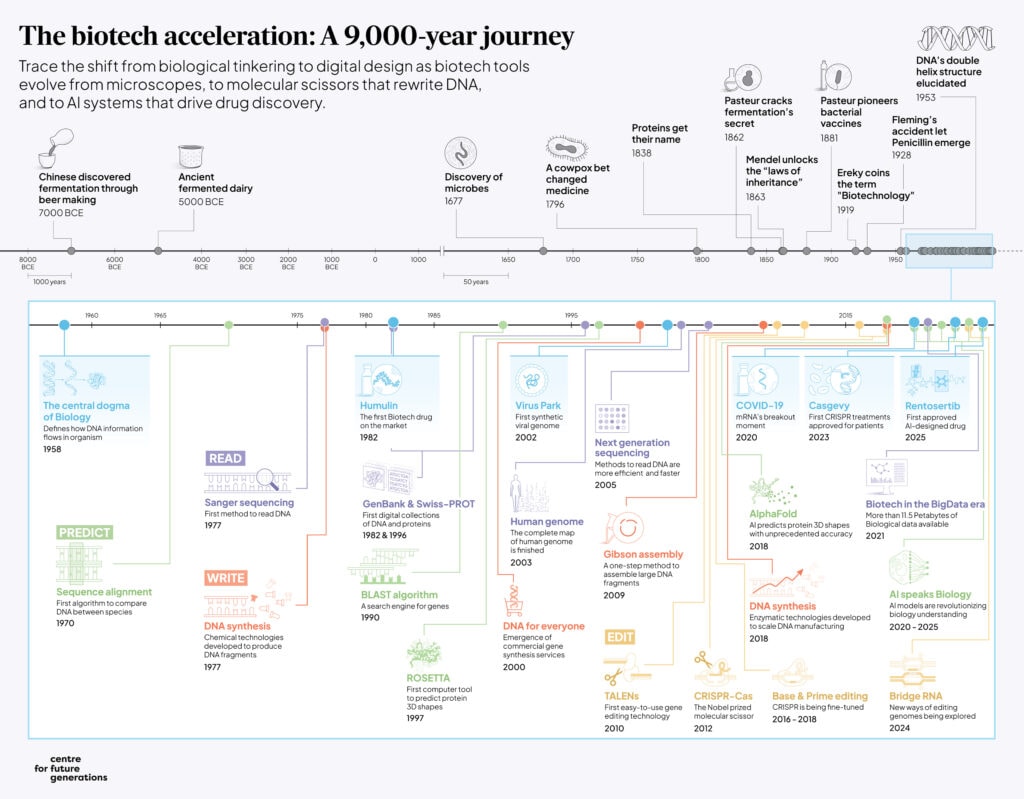

A brief history of biotechnology advancements

A striking feature of biotechnology’s evolution is the interdependence between innovations [2].

Early advancements unfolded in a step-by-step progression: the ability to see DNA enabled the ability to read it via sequencing; reading enabled the ability to write DNA (synthesis); and writing enabled the ability to edit it (genome engineering) [3]. These once-distinct capabilities now overlap and interact, creating feedback loops that compress development timelines and amplify technological capabilities. This evolution represents the culmination of centuries of discovery, where incremental leaps in understanding basic biology formed the foundation for today’s capacity to use biology to solve complex problems at scale 8.

As we stand at this technological convergence, it is worth looking at how we got here. This introductory piece opens with a brief tour of biotechnological developments and our evolving relationship with genetic material.

Like rooms in a museum, we’ll showcase the key moments when societies first learned to read biology’s language, gained the ability to write new biological instructions, developed tools that edit living systems, and now stand at the threshold of being able to predict biological outcomes. Each ‘exhibit’ highlights the scientific achievement as well as the governance challenges that come with it.

The foundations: learning to SEE

Biotechnology began with hungry humans and mouldy bread.

Stone Age brewers fermented grains into beer using wild yeast they couldn’t see. Roman farmers turned milk into cheese with microbes they called “spirits.” These were acts of applied biology, practical, but rooted in mystery and blindness like the potential usage of what we later called antibiotics[9].

Things changed when we learned to see the biology in front of us. In 1677, Leeuwenhoek’s microscope revealed a hidden ecosystem of “little creatures” in the environment[10]. While discussion about vaccination can be traced back to the 1500s in Asia[11], Jenner’s 1796 smallpox vaccine[12] proved to the world we could use biology against itself, decades before viruses had names. By 1865, Mendel’s pea plants hinted at the early principles of how traits are inherited in living organisms, a puzzle we wouldn’t fully crack for a century[13].

The rules of heredity became tangible in 1953 when Franklin, Watson, Crick, and Wilkins unveiled DNA’s double helix: a twisted ladder encoding the ‘instructions’ of living organisms[14]. This was biology’s “Big Bang” moment: suddenly, traits passed through generations were not abstract mysteries, but molecules we could map and eventually modify. Later in 1958 came the “central dogma” of Biology, the foundational rule that genetic information flows from DNA to RNA to proteins[15]. This gave this system a logic revealing the grammar of a language we had only glimpsed in fragments.

These breakthroughs did not just explain life; they laid the groundwork for today’s tools to READ, EDIT, WRITE and PREDICT biology.

The sequencing revolution: learning to READ

If seeing biology’s hidden world was the first step, the second turned scientists into keen readers. This shift didn’t just decode life’s manual; it flooded us with the biological data feeding today’s industries. The story began with Frederick Sanger’s 1977 breakthrough: sequencing DNA letter by letter, like transcribing an ancient scroll [16]. Suddenly, traits were sentences in a genetic manuscript. This opened the door to ambitious projects like the Human Genome Project—a 13-year endeavour delivering humanity’s first “genetic reference book”[17]. Next-Generation Sequencing went on to overhaul DNA sequencing by replacing slow, error-prone methods with fast automation [18]. By 2021, labs generated more genomic data monthly than the entire Human Genome Project produced in 13 years[19].

Biology had entered the Big Data era. This genetic tsunami now fuels precision medicine targeting unique mutations and AI models trained on biological libraries. Biological data has become a strategic resource for societies fostering biotech innovation. For policymakers, the message is clear: sequencing is not just science – it is data infrastructure. How we navigate ownership, protection, and governance of biological data will define the future of healthcare, global economies, and biotechnology itself.

The synthesis revolution: learning to WRITE

From laboriously printing DNA fragments to creating pandemic-ending mRNA vaccines in days, humanity’s journey from genetic readers to writers has rewritten biology’s rules and redefined biotech power.

By 1981, scientists developed a method using chemicals to build DNA molecules and helped to automate the ‘writing’ of genes through constructing DNA fragments [20]. In the early 2000s, a breakthrough borrowed from the computer industry transformed how we build DNA[21]. Biotechnology companies repurposed semiconductor manufacturing methods, the same techniques used to make microchips, to turn flat surfaces like glass slides into ultra-efficient DNA assembly lines [22], [23]. These advances let companies slash costs and democratize DNA synthesis[21][22].

Today, synthetic DNA can be ordered as easily as office supplies, thanks to streamlined manufacturing processes. The ability to write DNA became a cornerstone of biotechnology, transforming biology from a system we observe into one we engineer. Beyond medicine, applications now extend to agriculture, energy, and manufacturing, promising a future where bio-based products support transition from oil-plastic economies.

This bioeconomy is not speculative, it represents EUR 720 billion in 2021[24] and is expected to significantly grow in the future[25].

Yet every advance in this technology’s capabilities amplifies a paradox. The same DNA technologies promising to benefit society are in some ways open to misuse. In 2002, scientists created the highly contagious poliovirus from DNA fragments ordered by post[26]. DNA material which was once prohibitively expensive, was now costing less than a used car. Today, this accessibility creates tangible risks: indeed, commercial DNA synthesis providers lack universal, binding standards to screen orders for hazardous pathogens, while hobbyists can acquire DNA printers with minimal oversight. As biology becomes accessible to hobbyists, biotech’s power and threats share the same sliding scale[27].

Restricting scientific capabilities and knowledge is hardly an option. Policymakers are now tasked with crafting guardrails that enable safe innovation and stay aligned with our understanding of the opportunities and risks from this technology.

The CRISPR revolution: learning to EDIT

From 1973 scientists had crude tools that let them splice DNA between species, using Cohen and Boyer’s ‘molecular scalpels,[28]. The early 2000s brought incremental upgrades: gene therapy using viruses as biological couriers, and tools that cut genes with moderate precision [29], [30]. These instruments worked, but their complexity kept genetic editing rare, slow, and accessible only to scientific elites.

Then came CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats), a new way to do gene editing, in 2012. Scientists transformed a bacterial immune system into a genetic word processor[31]. Unlike earlier tools, CRISPR worked like a search-and-replace function for DNA: type a 20-letter genetic address, and the system cut there. Since its discovery over a hundred clinical trials are now testing gene editing for cancers, HIV, and genetic blindness 32. In 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first CRISPR therapy for sickle cell disease, a one-time edit correcting a single mutated letter causing lifelong implications [32], [33].

But precision cuts both ways. In 2018, a scientist edited human embryos to create HIV-resistant babies. This procedure was unnecessary given existing HIV prevention methods, technically flawed as it failed to confer reliable and demonstrated immunity, and ethically reckless as it was ignoring potential bystander effects as the target gene had been described to have known roles in brain function affecting memory- AKA explain those here [34], [35], [36]. It sparked global outrage[37] and exposed gaps in our governance systems.

Now, we find ourselves in an odd position.

CRISPR technology has become remarkably accessible to the general public[38], [39], [40]. For just a few hundred dollars, anyone can purchase DIY CRISPR kits online from companies, complete with all materials needed to genetically modify bacteria in their kitchen. These kits include the molecular tools, and bacterial cultures, allowing hobbyists to perform genetic engineering experiments that would have required a sophisticated laboratory just a decade ago38. Some biohackers have even livestreamed themselves injecting CRISPR components into their own bodies[41], attempting DIY gene therapy though the FDA has declared such self-administration illegal and potentially dangerous On the other hand, FDA-approved CRISPR-based therapies developed by biotechnology companies operate in an entirely different economic context. Casgevy, the first CRISPR therapy approved by the FDA costs $2.2 million per patient [42]. This price, justified by companies as reflecting development costs and the value of a potential lifetime cure, means these life-saving treatments remain financially out of reach for most patients, particularly affecting communities already facing healthcare disparities.

The challenge for policymakers is creating governance that can address a technology that simultaneously exists as an accessible tool for research and as a self-experimentation platform and as a multi-million dollar medical breakthrough, all based on the same underlying science. The regulatory questions become even murkier when we consider specific applications. Should, for example, using CRISPR to prevent Alzheimer’s disease be regulated the same way as using it to enhance intelligence? The line between therapy and enhancement, clear in theory, blurs in practice. Similarly, are gene-edited climate-resistant crops simply an acceleration of traditional breeding (and thus exempt from GMO regulations), or are they “GMOs 2.0” requiring stricter oversight? Appropriate governance needs iterative design, like CRISPR itself.

The AI revolution: learning to PREDICT

We are now surfing a new wave – using AI to design biology. This evolution started with scientists developing the first comparison tools for proteins 1970[43]. By the 1990s, this became BLAST (Basic local alignment search tool), a revolutionary system that acted like a “card catalog for genes,” letting scientists search a global library of DNA snippets in seconds[44]. Several statistical and computational methods were subsequently developed to map gene evolution – a technology that is one of the foundations of today’s AI models[45].

A breakthrough in protein design happened in 1997 with the release of the ROSETTA software: computers could predict how small proteins fold into 3D shapes[46]. But while this was a massive leap, capabilities remain pretty constrained and predictions inaccurate. It was only in 2018, with the release of AlphaFold, that scientists were able to leverage the power of AI to accurately predict 3D shapes [47]. This breakthrough turned years of lab work into minutes of computation. Today, AI does not just predict biology – it invents it, generating molecules and genetic blueprints previously unseen in nature[48], [49], [50],[51].

But as AI’s power in biology grows [52], policymakers are now faced with navigating the inherent dual-use dilemma[53] at the interface of AI and Biotechnology[54], [55]. AI is unlocking faster and more complex bioengineering projects – and the impact of those is less predictable than before. For example, when AI models learn how a virus can escape the host immune system, it could use that information to either design life-saving treatments or dangerous new pathogens[56]. To harness AI’s potential and benefits while preventing misuse, we must continuously track its evolving capabilities and adopt anticipatory model of governance [57] to establish the appropriate guardrails for its use in Biotechnology .

This story is not predetermined. Only with humble and thoughtful stewardship can we ensure biotechnology’s next chapter benefits humanity.

ASSISTing science: the next part of the technology revolution

But today’s frontier is also AI. By engulfing biological datasets, AI models can predict molecule designs no human might envision. Guided by the capabilities of our “write” platforms, scientists can synthesize and test new predicted therapeutic candidates. The result? Breakthroughs like Rentosertib, the first AI-designed drug to combat lung fibrosis, on the path for regulatory approval [58]. Rentosertib is just the start as hundreds of AI-designed therapies now advance through trials, targeting cancers, neurodegenerative disorders, and rare diseases. Yet these milestones are not isolated triumphs, but threads in biotechnology’s broader tapestry. CRISPR-based diagnostics, mRNA platforms democratizing vaccine development, automated labs turning hypotheses into therapies in days – every innovation rewrites humanity’s relationship with life itself. Progress, however, rests on invisible foundations: data infrastructures housing genomic libraries, biofoundries translating digital designs into physical therapies, and ethical frameworks ensuring these tools uplift all.

Large language models, research automation platforms, and laboratory robots are progressively becoming active participants in the scientific process. AI systems will not just analyse data; they will design experiments, generate hypotheses, and even operate laboratory equipment. [48], [49], [50],[51]. [52] [53] Research that today requires teams of specialists working for years may, in the future, be conducted in weeks by smaller teams augmented by AI assistants. As such, the boundaries between our established waves – seeing, reading, writing, editing, and predicting – are beginning to blur.

These new systems represent more than additional tools in the biotechnologist’s arsenal; they may trigger a fundamental shift in how biological research proceeds, where each insight immediately feeds back into algorithms, driving a virtuous cycle of innovation.

Weighing up innovation vs implementation

Through this accelerating technological convergence, we must confront a fundamental paradox in biotechnology: the existing gap between the speed of innovation and the pace of translating this innovation into real-world applications. The tempo of discovery has already accelerated dramatically. The gap between reading and writing in decades; between writing and editing in years. Today, design capabilities emerge almost simultaneously with new discoveries, as feedback loops between technology and knowledge tighten to near-instantaneous speeds. However, biotechnology ultimately operates at the pace of life.

While computational design can happen in seconds, testing biological implementations requires patient observation of living systems. A new gene therapy might be conceptualised in weeks, but scaling production to reach patients takes months or years. This dual tempo creates both opportunities and challenges for policymakers. On one hand, the rapid pace of discovery demands regulatory frameworks that can evolve quickly to address novel technologies. On the other hand, the inherent slow down involved in translating innovation into real-world applications provides a window for thoughtful assessment of risks and benefits. This inherent duality demands a particular form of wisdom from both scientists and policymakers.

We must embrace the transformative potential of converging technologies while maintaining a profound humility about biological complexity and acknowledging that each molecular innovation can echo far beyond the laboratory, across generations and ecosystems.

What comes next: the biotech Atlas

This introduction has given you a glimpse of biotechnology’s extraordinary evolution. But we’re just getting started. Over a series of posts, we’ll dive deep into each of the technologies described above. We will start first with the technologies that write biology, then the one that edits it and finally will finish on discussion about AI in biotech by describing the emerging technologies that can predict biology and assist the scientists. Each installment will equip you with the knowledge to understand and shape the policies governing these world-changing technologies. Subscribe now to ensure you don’t miss the next chapter in the biotechnology revolution.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the input and feedback received from Dr Paul-Enguerrand Fady (Centre for Long-Term Resilience) and Laurent Bächler (whilst at Pour Demain).

Endnotes

[1] S. Bodakuntla, C. C. Kuhn, C. Biertümpfel, N. Mizuno, Front. Mol. Biosci. 10, https://www.drugtargetreview.com/news/157365/first-ai-designed-drug-rentosertib-named-by-usan/”ho.int/publications/i/item/9789240018440″

[2] WHO. Genomic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2: a guide to implementation for maximum impact on public health. (2021).

[3] Joi, P. Using AI from lab to jab: how did artificial intelligence help us develop and deliver COVID-19 vaccines? (2025).

[4] Zhang, H. et al. Algorithm for optimized mRNA design improves stability and immunogenicity. Nature 621, 396–403 (2023).

[5] K. S. Corbett et al., SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. Nature. 586, 567–571 (2020).

[6] Voigt, C. A. Synthetic biology 2020–2030: six commercially-available products that are changing our world. Nat. Commun. 11, 6379 (2020).

[7] Verma, A. S., Agrahari, S., Rastogi, S. & Singh, A. Biotechnology in the Realm of History. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 3, 321–323 (2011).

[8] Bifulco, M., Zazzo, E. D., Affinito, A. & Pagano, C. The relevance of the history of biotechnology for healthcare. EMBO Rep. 26, 303–306 (2025). doi: 10.1038/s44319-024-00355-8

[9] Aminov, R. I. A Brief History of the Antibiotic Era: Lessons Learned and Challenges for the Future. Front. Microbiol. 1, 134 (2010).

[10] Robertson, L. A. Antoni van Leeuwenhoek 1723–2023: a review to commemorate Van Leeuwenhoek’s death, 300 years ago. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 116, 919–935 (2023).

[11] Boylston, A. The origins of inoculation. J. R. Soc. Med. 105, 309–313 (2012).

[12] Riedel, S. Edward Jenner and the History of Smallpox and Vaccination. Bayl. Univ. Méd. Cent. Proc. 18, 21–25 (2005).

[13] Mendel, G. Experiments in Plant Hybridization. (1865).

[14] WATSON, J. D. & CRICK, F. H. C. Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid. Nature 171, 737–738 (1953).

[15] F. H. CRICK, On protein synthesis, Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 12, 138–63 (1958).

[16] Sanger, F., Nicklen, S. & Coulson, A. R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 74, 5463–5467 (1977).

[17] Consortium, I. H. G. S. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature 431, 931–945 (2004).

[18] Goodwin, S., McPherson, J. D. & McCombie, W. R. Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 333–351 (2016).

[19] Sayers, E. W. et al. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D20–D26 (2021). DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkab1112

[20] Matteucci, M. D. & Caruthers, M. H. Synthesis of deoxyoligonucleotides on a polymer support. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103, 3185–3191 (1981).

[21] Egeland, R. D. & Southern, E. M. Electrochemically directed synthesis of oligonucleotides for DNA microarray fabrication. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, e125–e125 (2005).doi: 10.1093/nar/gni117

[22] S. Kosuri, G. M. Church, A. Hoose, R. Vellacott, M. Storch, P. S. Freemont, M. G. Ryadnov, Nat. Rev. Chem. 7, 144–161 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-022-00456-9

[23] Hoose, A., Vellacott, R., Storch, M., Freemont, P. S. & Ryadnov, M. G. DNA synthesis technologies to close the gene writing gap. Nat. Rev. Chem. 7, 144–161 (2023).

[24] E. Commission, “Building the future with nature: Boosting Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing in the EU” (2024).

[25] McKinsey. The Bio Revolution. (2020).

[26] J. Cello, A. V. Paul, E. Wimmer, Chemical synthesis of poliovirus cDNA: generation of infectious virus in the absence of natural template Science. 297, 1016–1018 (2002). DOI: 10.1126/science.1072266

[27] Scroggins, M. A feral science? Dangers and disruptions between DIYbio and the FBI. Crit. Anthr. 43, 84–105 (2023).

[28] Cohen, S. N., Chang, A. C. Y., Boyer, H. W. & Helling, R. B. Construction of Biologically Functional Bacterial Plasmids In Vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 70, 3240–3244 (1973).

[29] Cavazzana-Calvo, M. et al. Gene Therapy of Human Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID)-X1 Disease. Science 288, 669–672 (2000).

[30] Miller, J. C. et al. A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 143–148 (2011).

[31] Jinek, M. et al. A Programmable Dual-RNA–Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity. Science 337, 816–821 (2012).

[32] Singh, A. et al. Revolutionary breakthrough: FDA approves CASGEVY, the first CRISPR/Cas9 gene therapy for sickle cell disease. Ann. Med. Surg. 86, 4555–4559 (2024).

[33] Davies, K., Philippidis, A. & Barrangou, R. Five Years of Progress in CRISPR Clinical Trials (2019–2024). CRISPR J. 7, 227–230 (2024).

[34] Antonio Regalado. China’s CRISPR babies: Read exclusive excerpts from the unseen original research (2019).

[35] Greely, H. T. CRISPR’d babies: human germline genome editing in the ‘He Jiankui affair’*. J. Law Biosci. 6, 111–183 (2019).

[36] Zhou, M. et al. CCR5 is a suppressor for cortical plasticity and hippocampal learning and memory. eLife 5, e20985 (2016).

[37] Marx, V. The CRISPR children. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 1486–1490 (2021).

[38] Guerrini, C. J., Spencer, G. E. & Zettler, P. J. DIY CRISPR. North Carolina Law Review (2019).

[39] A. Sneed. Mail-Order CRISPR Kits Allow Absolutely Anyone to Hack DNA. (2017)

[40] C. J. Guerrini, G. E. Spencer, P. J. Zettler, DIY CRISPR North Carolina Law Review (2019).

[41] K. Schroeder. Biohackers’ and DIY Gene Therapy. (2022)

[42] N. Pagliarulo. Pricey new gene therapies for sickle cell pose access test. (2023)

[43] 1. S. B. Needleman, C. D. Wunsch, J. A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequence of two proteins Mol. Biol. 48, 443–453 (1970).

[44] S. F. Altschul, W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, D. J. Lipman, J. Basic local alignment search tool Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

[45] D. J. Lipman, S. F. Altschul, J. D. Kececioglu, A tool for multiple sequence alignment Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 86, 4412–4415 (1989).

[46] K. T. Simons, C. Kooperberg, E. Huang, D. Baker, J. Mol. https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article%3D6743%26context%3Dnclr” al., Nature. 577, 706–710 (2020).

[47] Senior, A. W. et al. Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature 577, 706–710 (2020).

[48] Hayes, T. et al. Simulating 500 million years of evolution with a language model. Science 387, 850–858 (2025).

[49] Nguyen, E. et al. Sequence modeling and design from molecular to genome scale with Evo. Science 386, eado9336 (2024).

[50] Watson, J. L. et al. De novo design of protein structure and function with RF diffusion. Nature 620, 1089–1100 (2023).

[51] F. Braza. When left becomes right: the science of mirror life. Centre for Future Generations, (2025).

[52] Villalobos, P. & Atanasov, D. Announcing our Expanded Biology AI Coverage. (2025).

[53] A. Noriega, F. Braza. The Age of AI in the Life Sciences. National Academies (2025).

[54] Sciences, C. on A. and N. B. C. and B. of A. I. U. in the L. et al. The Age of AI in the Life Sciences. (2025) doi:10.17226/28868.

[55] Wheeler, N. E. Responsible AI in biotechnology: balancing discovery, innovation and biosecurity risks. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 13, 1537471 (2025).

[56] Thadani, N. N. et al. Learning from prepandemic data to forecast viral escape. Nature 622, 818–825 (2023).

[57] OECD. Framework for Anticipatory Governance of Emerging Technologies. OECD Sci., Technol. Ind. Polic. Pap. (2024)

[58] FDA, FDA Approves First Gene Therapies to Treat Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. (2023).

[59] Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Innovative Genomics Institute Announce New Center for Pediatric CRISPR Cures. (2025).

[60] Drug Target Review, First AI-designed drug, Rentosertib, officially named by USAN. (2025).

[61] Jayatunga, M. K. P., Xie, W., Ruder, L., Schulze, U. & Meier, C. AI in small-molecule drug discovery: a coming wave? Nat Rev Drug Disc (2022) DOI: 10.1038/d41573-022-00025-1

[62] Skarlinski, M. D. et al. Language agents achieve superhuman synthesis of scientific knowledge. arXiv (2024)

[63] Swanson, K., Wu, W., Bulaong, N. L., Pak, J. E. & Zou, J. The Virtual Lab: AI Agents Design New SARS-CoV-2 Nanobodies with Experimental Validation. bioRxiv 2024.11.11.623004 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.11.11.623004

[64] Adam, D. The automated lab of tomorrow. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2406320121 (2024).

[65] Boiko, D. A., MacKnight, R., Kline, B. & Gomes, G. Autonomous chemical research with large language models. Nature 624, 570–578 (2023)

[66] Bran, A. M. et al. Augmenting large language models with chemistry tools. Nat. Mach. Intell. 6, 525–535 (2024)

[67] Narayanan, S. et al. Aviary: training language agents on challenging scientific tasks. arXiv (2024)