Why the Commission must think bigger on CERN for AI

Earlier this month, former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi added to the call for EU action, warning “the risk for Europe is to be totally dependent on AI models designed and developed abroad”.

Now, members of von der Leyen’s new team have been charged with making the idea a reality.

Academia and industry alike have expressed support for this initiative, but it remains a concept in search of detailed recommendations. There have been previous proposals for a CERN for AI, but these focused narrowly on AI usage in science and academia.

We at the International Centre for Future Generations, a Brussels-based think tank dedicated to ensuring emerging technologies are harnessed to serve the best interests of humanity, recently published an analysis suggesting this initiative should be far, far bolder.

With the right level of ambition, CERN for AI could help incoming executive vice presidents Stéphane Séjourné and Henna Virkkunen deliver on their ambitious portfolios. Setting up a European institute capable of producing world-leading trustworthy AI models could give the EU a multi-trillion euro market share in a crucial general purpose technology.

This immense value is rooted in how indispensable advanced AI is becoming to the functioning of Europe’s economies, democracies, and security. Given this, a well-designed CERN for AI could effectively promote the EU’s prosperity, technology sovereignty, security, and democracy.

There are many crucial elements to consider in a CERN for AI fit for this purpose, but four are particularly critical: scale, entrepreneurial leadership, security, and benefit-sharing.

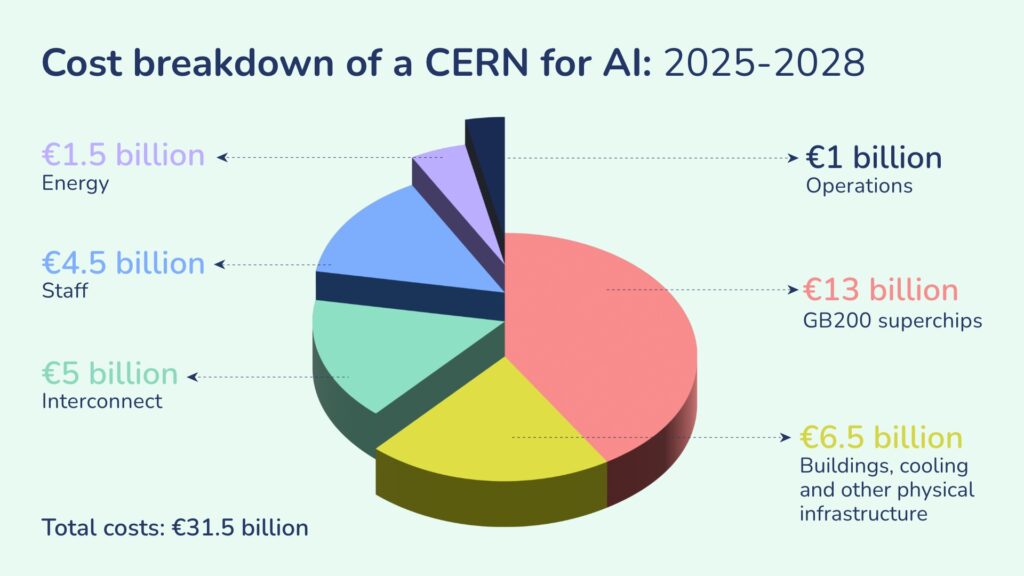

The importance of scale can’t be overstated. A CERN for AI requires substantial investment and ambitious goals to compete globally. To be competitive with the leading private companies by 2026, we must focus on the crucial AI infrastructure. It would be likely to need to acquire some 200,000 NVIDIA GB200 superchips, all located in a maximum of five geographically separated campuses that are linked by high bandwidth connections.

More ambition

This is an order of magnitude more ambitious than the compute investments from the EuroHPC AI Factories programme, but it does make sense in a wider landscape of “radical change” in EU industrial policy, as Draghi has put it. In fact, public AI infrastructure investments form a logical continuation of the comparably capital intensive EU Chips act: Europe not only needs a domestic chip manufacturing industry, it also needs a domestic AI industry that builds applications on those chips.

Strong entrepreneurial leadership is also essential. Without the people to make this project work, infrastructure investments will not do the trick.

There is intense competition for AI skills. A recent study indicates that 55% of top AI talent is located in just the US and UK and the race between the world’s largest tech companies will only create further competition. It is easy to imagine a public sector AI project being outrun in the talent stakes. One way to resolve this is to follow the example of the UK and US AI Safety Institutes in employing prominent AI researchers like Geoffrey Irving and Paul Christiano, inspirational scientific figures who can attract top technical talent.

The next pitfall would be failing to deliver the crucial infrastructure in time – a chronic problem within the EU, from energy, to transport and telecomms, to cloud computing. Getting somebody who has hands-on experience of the AI clusters the EU needs is likely to mean importing talent from industry; the Commission must be brave enough to bring that expertise into the public sector.

Political buy-in

Layered on these practical issues, are various concerns about political buy-in. CERN for AI is a massive commitment. It requires ambition and far-sighted leadership. It will involve the coordination of a coalition of leaders from polities that are undergoing significant upheavals either at the ballot box or in their economies. Picking a chair who has the skills to navigate this complex political landscape will be vital to avoid costly delays.

In addition, robust multi-level security measures are paramount. Employing a tiered structure for security and access could balance open research with protecting sensitive work. Top level security measures are indispensable to safeguard the critical research and information underpinning Europe’s AI advancements. On the more open tier, public-private partnerships can leverage private sector expertise to translate foundational research into applications in robotics, science and public services. In this sphere, CERN for AI could swiftly leapfrog industry leaders, as indicated by a recent RAND analysis, given leading AI companies are far more focused on investing in capability than they are in safety.

Finally, an attractive benefit sharing structure could ensure the investment is worthwhile for the EU and participating companies. A shareholder system paying dividends from commercialisaed models and making data sets and research available to participating companies and countries, would distribute the economic and technological gains fairly among members.

In order for a shareholder system to work, CERN for AI will have to generate revenues. CERN for AI’s foundational research will benefit the economy on a wider scale, for example through productivity and efficiency gains in the public sector. However, CERN for AI will also carry out applied and applications-driven research, which can be more directly commercialised. These revenue streams can then be reinvested into further research or used to lower individual taxpayer bills.

Europe’s last chance

A CERN for AI could still train large, multimodal models like those currently on the market. Training such models will yield economic value, especially if they can be fine tuned and personalised for different European audiences. This will enable researchers to build experience with large scale projects involving difficult hardware challenges. It is crucial though, that the institute doesn’t lose track of the overarching goal, which should always be to invent truly trustworthy AI. The project has a unique opportunity to diversify the advanced AI landscape because it will be designed to deliver societal, not shareholder, value, thereby avoiding many of the dangerous competitive dynamics the leading AI companies are embroiled in.

This might be the EU’s last chance to catch up with foreign advanced AI developers. In the US and China, large scale public and private investments are flowing into AI and the semiconductors the AI models are trained on. Without a large, dedicated European effort, these nations will solidify their leads. Catching up will only become more and more expensive the longer the EU waits.

CERN for AI should be understood not just as an ambitious technology project, but as a crucial step to secure Europe’s economic future, safeguard its security and geopolitical standing, and steering the trajectory of AI development towards more trustworthy and ethically aligned systems.