The European Commission needs a Chief Operating Officer

Put differently, an organisation’s skills and resources need to be proportionate to its objectives. Seventy years later, this rule is broken within the Institutions of the European Union.

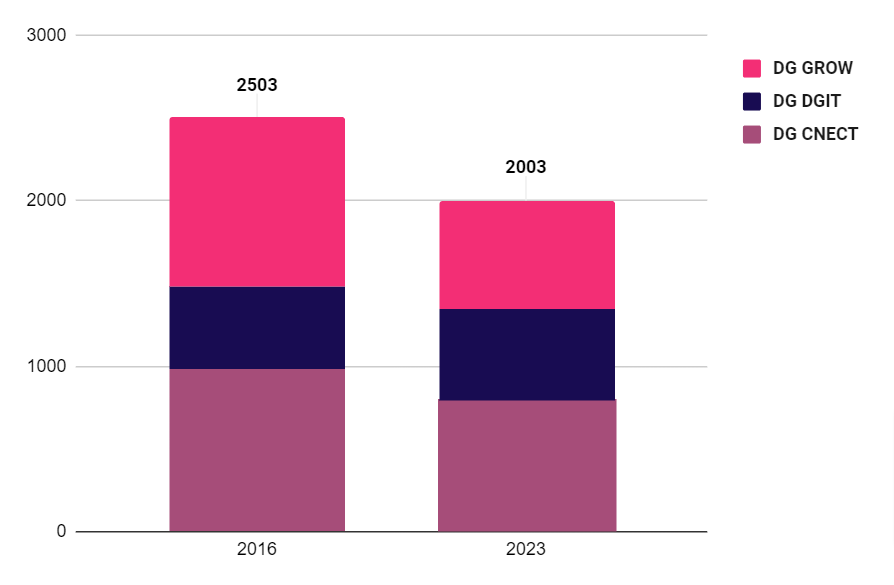

Some basic institutional math reveals an impossible mismatch between aspirations and capabilities. According to official sources, today the European Commission has around 32,000 employees. That’s the same number as in 2016. Yet, the scope and complexity of the portfolios has increased.

This trend is not exclusive to EU Institutions. A global survey of civil servants reports that the majority of government staffers find that climate change is impacting their work. Still, they have not received specialised training to handle the related additional complexity and demands.

Nowhere is this more evident than in digital policy. In the past decade, Brussels has made its name globally by passing several comprehensive regulations on data protection, online platforms, AI, and interoperability. However, the hiring of specialised talent has not come alongside this explosion of legislative activities in often incredibly technical domains.

All this technology policy has not resulted in more technologists among public servants. In fact, the share of staff in the responsible Directorates has, shockingly, actually shrunk between 2016 and 2024.

The European AI Office was supposed to reverse this trend. Yet, thus far, it has limited itself to a remix of the existing organisational chart rather than a much-needed bolstering of resources and authority. The office opened calls to recruit “Technology Specialists,” but those positions will only be a minority. With exponential developments in Generative AI, the gap between skills and needs will likely widen.

Rationalising resources in response to calls to cut red tape should not mean spreading them thinner. In that sense, the European civil service has punched above its weight, toggling an increasing number of policy goals with the same few hands. But passing policies is far from the end of the process – as my colleagues at ICFG puts it, “their true value lies in their comprehensive implementation and effective enforcement.”

Rationalising public service means proportioning the right staff for the right job. It means hiring technologists and lifting implementers from the industrial-age into the AI-age. And it takes aligning institutional means with political ends.

We need a Commissioner dedicated to creating state capacity in order to achieve these tasks. Building such capacity within the Institutions needs to become a political priority, rather than a technical requirement. And realising the mission will necessitate a change in incentives and the acquisition of new skills, rather than just a remix of organograms.

Building “state capacity” isn’t a rehashing of age-old debates about reducing administrative burden and “cutting red tape”. State capacity is the ability of an institution to enforce its mission. In the words of Jennifer Pahlka, former Deputy-Chief Technology Officer during the Obama administration:

In her book Recoding America, Pahlka, who is best known for rescuing the rollout of healthcare.gov after its initial crash, argues that effective implementation requires a shift from project management to product management:

The Commission needs new ways to flexibly hire the right talent for the right job, the same way the White House could recruit rockstar engineers from Big Tech to bolster government services. This talent needn’t be concentrated in a Digital Service, but spread across the civil service to enable the growing number of departments that are required to tackle more and more complex challenges.

There are precedents. President Obama launched the Presidential Innovation Fellowships, for example. Singapore and Estonia employ similar schemes. They mitigate the problem of revolving doors with clauses that prevent an individual from working in an area where there would be conflicts of interest — and watchdogs to enforce them.

In 2016, the Italian government turned a Senior Vice-President from Amazon into its Extraordinary Commissioner for Digital Transformation. It entrusted him with the freedom to hire the right people to modernise government. The license to build paid off: Italy had an exponential growth in e-Government users in the past five years, surpassing the EU average.

A Commissioner for institutional capacity would give transformation projects and their missionaries the political sponsorship they need to succeed.

Precedents even exist within the Institutions. DG Competition has a Chief Technology Officer with a mandate to support policymaking with products. But what the Commission needs is a policy-entrepreneur-in-chief with the highest political mandate. That person’s job will be to turn the digital transformation of the Institution into a whole-of-government priority, as attempted with Fit for 55.

DG DIGIT has become the Directorate for “Digital Services,” a recognition of its role in enabling transformation for users, rather than merely buying laptops or making forms paperless. DG DIGIT has, in fact, become an international reference for innovating the way it brokers cloud services at scale. Lately, it has been the driving force behind the European Commission’s Digital Strategy which led to the European Interoperability Act: a first-of-its kind regulation that aims to allow innovation to move freely across Member States.

These facts are little-celebrated within Institutions, a testimony to the low regard given to implementers. These implementers would have the highest clout and the highest pay in big tech firms. The lack of operational excellence means slower innovation, which makes customers dissatisfied and competitors happier. The challenges of governments are obviously more complex, but the need for implementers remains.

Under-investment in institutional capacity is somewhat surprising, in light of the ascent of the Directorate-General for Reform as one of the most important arms of the Commission, tasked with assisting Members States in growing state capacity in strategic areas. Last year, The Commission published a Communication to support a modern and effective public administration. That mission should apply to the European Commission too, with the same ownership and focus which is making some Directorates successful.

The realisation that transformation is not just for the geeks seems to be spreading. On 21 May, the European Council underlined “the need for digital government, driven forward by the human-centric, data driven and AI-enabled transformation of the public sector.” It even called upon “the Commission to put digital-ready policymaking in practice through guidelines, tools and trainings with the aim to bridge the gap between policy design and implementation.”

Competitiveness has already become the new mantra for the next European Commission. But discussion of the competitiveness of the European Commission, as an institution, is absent.

Here is a simple message to the incoming Presidency: physician, heal thyself.