Europe’s blind spots: The critical tech investments the EU can’t afford to miss

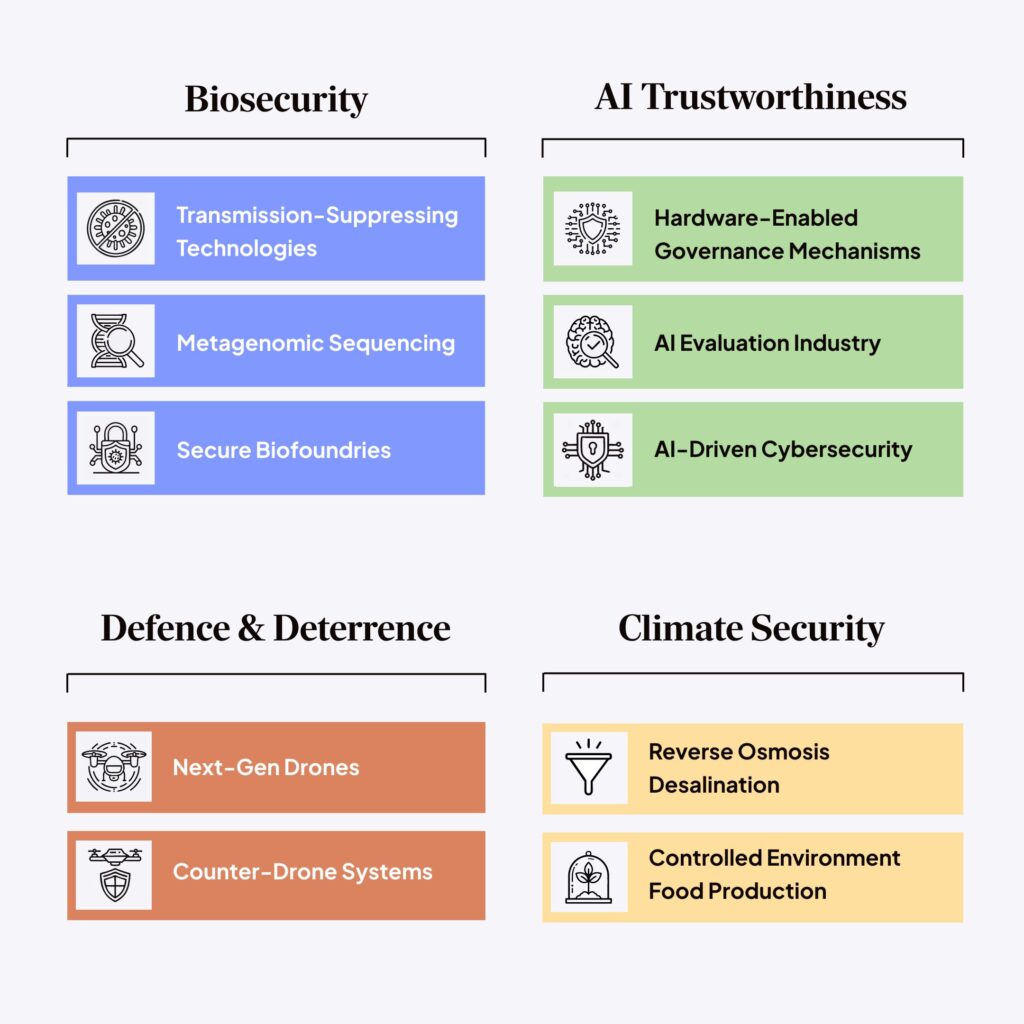

This commentary is part of our project Strategic innovation for European security. The project identifies ten emerging technologies the EU should invest in to safeguard its security and uphold European values in the face of rapid technological change, geopolitical instability, and economic uncertainty.

In an era marked by rapid technological evolution, geopolitical instability, economic uncertainty, and a burgeoning climate crisis, the European Union faces several challenges that threaten its security and prosperity. Two landmark reports – the Niinistö and Draghi reports – have emphasised the need for the EU to take on a more proactive role in strategic technology investments in order to navigate this complex landscape, enhancing its crisis preparedness and unlocking economic growth.

- The Niinistö report emphasised the need for the EU to “safeguard its ability to access, develop, operate, produce and secure critical goods and technologies” in order to bolster its crisis resilience[1].

- The Draghi report further noted that “the EU is weak in the emerging technologies that will drive further growth” and will have to develop “industrial partnerships to secure the supply chain of key technologies” in order to ensure its future growth and security[2].

Strategic innovation for European security addresses these calls to action.

Our aim is to support the EU’s mission to remain economically and technologically competitive, while also strengthening preparedness against emerging and systemic risks. The 10 technologies covered in this report are not an exhaustive list of the investments needed to ensure European competitiveness and resilience, but rather a focused set of high-upside bets in areas where emerging technologies are rapidly reshaping the competitiveness and security landscape.

Strategic investment in emerging technologies is a road to safety

The convergence of geopolitical tensions and emerging paradigm-changing technologies carrying transnational risks makes Europe’s security inseparable from its technological sovereignty. The EU faces a combination of threats that are staggering in their scale and complexity:

- Biosecurity is a rising concern, as the COVID-19 pandemic exposed gaps in Europe’s preparedness and its reliance on international supply chains. There is a clear and present risk of future pandemics and biological attacks, especially as advances in synthetic biology continue to make synthetic DNA more widely accessible[3].

- Defence and deterrence has become a topic of concern after Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine and the US’ foreign policy shift away from Europe, leading the EU and its Member States to make historic investments in its defence industry to meet a new geopolitical environment. These geopolitical developments coincide with rapid technological innovations within drone warfare and military AI, necessitating a proactive and strategic investment response in order to ensure European security going forward[4].

- Artificial Intelligence further introduces significant security risks alongside deeper uncertainties concerning the trustworthiness of frontier models. Policy-makers today must account for a diverse range of risks ranging from unpredictable algorithmic behavior to the potential loss of strategic advantage, particularly as the EU has fallen behind geopolitical peers in AI development[5].

- Climate security will further be a major security concern going forward, as the unavoidable consequences of climate change act as a threat multiplier. More extreme weather events – including floods and prolonged and intensified droughts and heatwaves – combine with non-climactic risks to threaten European food security and fresh water access, and thereby its public health and economic performance[6].

These challenges are too large for any one Member State to tackle alone. In fostering policy cohesion and coordinating investment, the EU is therefore a crucial actor in addressing the major security issues of our time. Both in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and in marshalling Europe’s collective support for Ukraine, the EU has demonstrated a capacity to coordinate crisis management across the Union. However, the EU has too often been caught unprepared and had to react after the fact. As urged by Niinistö: “We need to move from reaction to proactive preparedness[7]”.

Strategic investment in emerging technologies is a road to economic growth

Europe’s technological competitiveness gap has undermined its economic growth over the past few decades. During the first quarter of the 21st century, the gap between the EU and US in economic growth and productivity has widened, as Europe “largely missed out on the digital revolution led by the internet and the productivity gains it brought”[8]. The examples of a lagging Europe are numerous, and the EU’s lack of investment in tech is now being repeated within AI, biotech and R&D in general. The EU invested only 4% of what the US have invested in AI prior to 2025, and venture capital funding for AI was only €8 billion in 2023, compared to €68 billion in the US and €15 billion in China[9]. Likewise, within biotechnology, the EU has seen its share of global R&D spending drop from 41% to 31% over the past two decades, losing ground to the US and China. In 2002, the US spent €2 billion more on R&D within biotechnology than Europe, a gap that has since increased to €25 billion[10].

Further, the EU struggles to scale companies within its borders. Fragmentation in the single market, insufficient corporate risk-taking, lack of R&D investment, and strident regulations has limited the ability of European companies to scale and compete globally[11]. Many European companies have been driven to seek funding and scale their business by relocating to the US[12] and no EU company established in the past 50 years has reached a market capitalization of over €100 billion while remaining in Europe[13].

In order for the EU to counteract this trend, the Draghi report argues for a paradigm shifting expansion in EU research and innovation investment. This includes increasing Europe’s investment share by 5 percentage points relative to its GDP – an even larger increase in investment than the contribution from the Marshall Plan in the wake of WWII[14]. Additionally, the report argues for a doubling of the funding for the EU’s research and innovation programme to €200 billion in the next cycle, coupled with a focus on disruptive, future-defining technologies delivering breakthrough innovation[15].

Strategic investment in innovation today can drive Europe’s economic competitiveness for the future, driving productivity growth and sustainable prosperity for decades to come.

Strategic innovation to accelerate the european mission

Through strategic innovation, the EU can reduce risks from transformative technologies by influencing their direction and sequence of development. By accelerating the development of protective and safety-favoring technologies relative to potentially harmful ones, the EU can steer technological innovation towards greater societal benefit and security, effectively safeguarding European values such as democracy and fundamental rights. The efficacy of this is demonstrated by historical examples such as the seatbelt. Had such safety innovations been developed concurrently with groundbreaking but hazardous technologies like automobiles, hundreds of thousands of lives could have been saved[16]. By differentially accelerating the development of the technologies outlined in this report, European competitiveness can go hand in hand with human flourishing, democratic stability, and security, proactively mitigating risks before they materialize.

Strategic Innovation for European Security supplements EU’s effort by identifying a series of technologies with an outsized potential to simultaneously bolster the EU’s safety, and economic growth.

As a conservative estimate – and only if they are properly supported and scaled – the 10 identified technologies have the potential to save 220,000 lives in the EU per year, mitigate annual economic risks of €150bn in the EU, while adding €460bn per year to the European GDP in 2040[17].

These are indicative figures that would require further modelling and research to fully verify, but we include them to provide an indication of the approximate magnitude of the significance of the technologies included in this project.

Read the next part of this series here.

Endnotes

[1] Niinistö, S. ‘Safer Together: Strengthening Europe’s Civilian and Military Preparedness and Readiness’, European Commission, 2024. https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/5bb2881f-9e29-42f2-8b77-8739b19d047c_en?filename=2024_Niinisto-report_Book_ VF.pdf, p. 44.

[2] Draghi, M. ‘The future of European competitiveness’, European Commission, 2024. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en, pp. 1 & 13.

[3] Wickiser, J. K., et al. ‘Engineered Pathogens and Unnatural Biological Weapons: The Future Threat of Synthetic Biology.’ CTC Sentinel, 2020. https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/CTC-SENTINEL-082020.pdf

[4] Bondar, K. ‘Ukraine’s Future Vision and Current Capabilities for Waging AI-Enabled Autonomous Warfare’, CSIS, 2025. https://www.csis.org/analysis/ukraines-future-vision-and-current-capabilities-waging-ai-Enabled-autonomous-warfare (accessed 3 April, 2025)

[5] UK Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. International AI Safety Report 2025, 2025. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/679a0c48a77d250007d313ee/International_AI_Safety_Report_2025_accessible_f.pdf

[6] European Environment Agency, European Climate Risk Assessment, 2024. https://www.eeaeuropa.eu/en/analysis/publications/european-climate-risk-assessment (accessed 3 April 2025)

[7] Niinistö, S. ‘Safer Together: Strengthening Europe’s Civilian and Military Preparedness and Readiness’, European Commission, 2024. https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/5bb2881f-9e29-42f2-8b77-8739b19d047c_en?filename=2024_Niinisto-report_Book_ VF.pdf, p. 6

[8] Draghi, M. ‘The future of European competitiveness’, European Commission, 2024, p. 1. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en

[9] European Commission: EISEMA. ‘The EU invests in artificial intelligence only 4% of what the U.S. spends on It’. Newsroom, 2025. https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/eismea/items/864247/en (accessed 3 April 2025)

[10] Wilsdon, T., et al. ‘Factors affecting the location of biopharmaceutical investments and implications for European policy priorities’, Charles River Associates, 2022. https://www.efpia.eu/media/676753/cra-efpia-investment-location-final-report.pdf (accessed 3 April 2025).

[11] Digital Europe. The EU’s Critical Tech Gap: Rethinking economic security to put Europe back on the map, 2024. https://www.digitaleurope.org/resources/the-eus-critical-tech-gap-rethinking-economic-security-to-put-europe-back-on-the-map/ ; Smit, S., et al.‘Securing Europe’s competitiveness: Addressing its technology gap’, Mckinsey Global Institute, 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/securing-europes-competitiveness-addressing-its-technology-gap (accessed 3 April 2025)

[12] Accordingly, 30% of European startups that went on to be valued at over $1 billion relocated abroad between 2001 and 2021: Draghi, (2024).

[13] Draghi, M. ‘The future of European competitiveness’, European Commission, 2024, p. 2. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en

[14] Draghi, M. ‘The future of European competitiveness’, European Commission, 2024, p. 1. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en

[15] Draghi, M. ‘The future of European competitiveness’, European Commission, 2024, pp. 25 & 29. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en

[16] Based on more than 300,000 lives saved by seatbelts from 1960 to 2012 in the US alone: NHTSA. ‘Seat Belts Save Lives’, United States Department of Transportation, 2013. https://www.nhtsa.gov/seat-belts/seat-belts-save-lives (accessed 3 April 2025)

[17] Based on the total annualized impact estimates of the 10 technologies throughout the report. The key contributor to lives saved is pandemic prevention in biosecurity (we do not estimate lives saved for defence & deterrence, climate security, nor for AI security due to unreasonable uncertainty in the estimates). Please see our note on estimates in the methodology for more information.