Enforcement in an age of accelerated innovation

Introduction

Over the last decade, the EU has emerged as a global leader in technology policy, ushering in a wave of new digital and data laws—many of them first-of-a-kind, landmark legislations—that together form a strong legal basis underpinning Europe’s markets and societies. From the flagship data protection law (General Data Protection Regulation) to online platform regulation (Digital Services Act), to modernising digital competition (Digital Markets Act), to the world’s first artificial intelligence law (Artificial Intelligence Act), these laws underscore the EU’s commitment to fostering innovation, protecting fair markets, and safeguarding democratic principles, setting the stage for a more secure and human-centric digital future.

While the decade’s focus has been on the passage of these laws, however, that’s really only the beginning: their true value lies in their comprehensive implementation and effective enforcement.

Challenges to effective enforcement

Making all that technology policy truly valuable is still a challenge. It is already difficult to enact one law across 27 different member states, all with varying contexts, national laws, and regulatory approaches. Add to this a whole suite of new, first-of-a-kind laws targeting international actors including corporations of unprecedented size and reach, all against a backdrop of accelerating technological innovation, and it becomes clear: there is a chance that these policies never fully make it off the page. We need to address these challenges while we can, and improve and innovate enforcement where we can to make the most of this pathbreaking legal framework for technology.

Challenges to effective enforcement are well known. Procedural frameworks that sound good on paper but prove to be bureaucratically burdensome and inefficient in practice—or weakened by corporate capture. Bottlenecks within institutions. Lack of sufficient resourcing or insufficient independence of regulators, lengthy court procedures or appeals—all of these can all delay, obscure, and undermine the intended spirit of the law.

For example, the GDPR has prompted changes in business practices and increased awareness of data rights in Europe and beyond, but researchers like those at Utrecht University have found its enforcement has been uneven and privacy advocates like those at the Irish Council for Civil Liberties have reported its enforcement as largely unsubstantial. As a result, the GDPR has not yet had the intended impact on reshaping data-driven business models and behaviours, nor on truly enabling citizen control of privacy.

If the latest GDPR complaint filed against OpenAI by NOYB (None of Your Business) over AI ‘hallucinations’ follows a similar path to Max Schrems’ 2013 complaint against Facebook over unlawful data transfers, it may be another 10 years before OpenAI is held to account through EU lawmaking. While we don’t know how AI systems will develop in the next 10 years, we do know that they are developing very rapidly, that they are becoming increasingly accessible, and that the harms that developers and users can inflict on citizens and societies with AI are very real. 10 years is too long.

Without robust enforcement, the objectives of these groundbreaking laws—from protecting the integrity of the internal market, to promoting the transition to a digital and greener Europe, to safeguarding human rights and democratic values—are completely undercut. “We still need to sort a lot of this out,” says Jeremy Godfrey, head of the Irish Media Commission, but “there’s an immense amount of goodwill and desire for this to lead to effective regulatory collaboration.”

With a new EU mandate around the corner and ever more impactful technologies on the horizon, now is the time to leverage the EU’s technology laws by streamlining, improving, and innovating around enforcement in order to ensure that there are real-world impacts of democratic oversight.

Ideas for harnessing enforcement

With an EU tech policy bedrock now in place with strong and ambitious objectives in sight, the upcoming EU mandate should focus on harnessing these enforcement opportunities. It is time to draw from experience and foster innovative strategies that resonate across borders, technologies, and generations.

Looking ahead, member states are already urging the next Commission to prioritise holistic implementation and enforcement of these landmarks. Top brass at the Commission are talking a big game about being a strong enforcer, “from end to end” to avoid contradiction between laws, “connecting the dots” to harnessing synergies across laws, and “being a coherent implementer” of the new legislative framework.

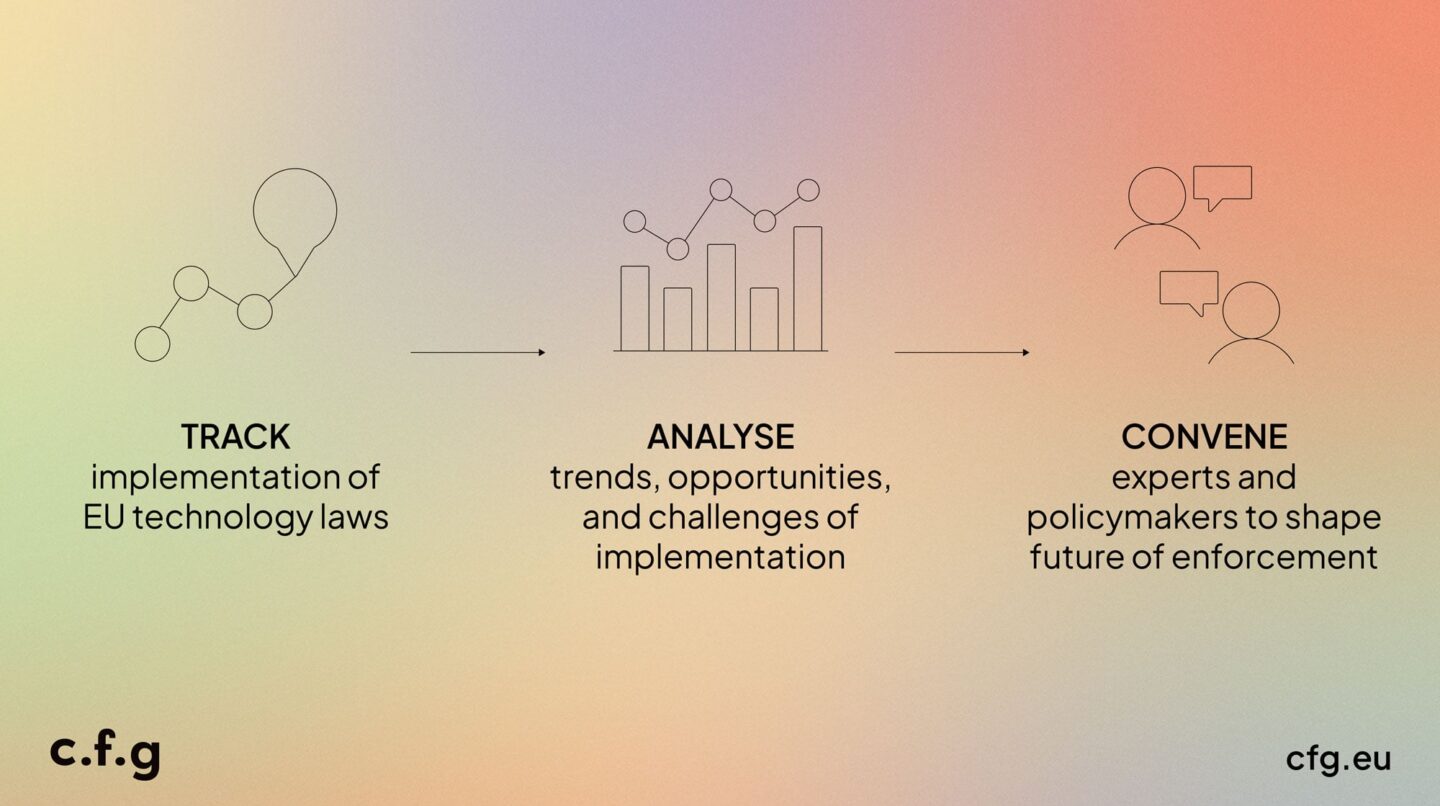

To support the EU enforcement ecosystem in making this a reality, ICFG is launching an enforcement initiative to support the EU’s ability to enforce its growing portfolio of digital regulation.

With this initiative, ICFG will track what constitutes effective enforcement, foster knowledge sharing and development for bridging potential skills shortages, guide discussions across sectors and borders on how enforcement challenges can be overcome, and rigorously analyse how to improve enforcement for a stronger digital future.

To start with, here are four ideas for how to harness enforcement for the public’s interest, which we call the Four “P’s” of Effective Enforcement: Policy, Practice, People, and Politics.

Policy: Ensure enforceability in the written laws

To enable enforcement, laws must be clear, actionable, and adaptable to evolving realities. This requires legal clarity—not tossing hot potatoes to delegated acts or secondary legislations—to avoid ambiguities or overlaps that set unclear expectations for compliance or delay enforcement efforts. This can be a real challenge with tech related legislation, which risks being outdated before laws are even passed. Technical specifications must be fundamental enough to ensure the law is future proof, or fit to apply in such an age of accelerating innovation. We’ve seen this most recently with the AI Act after the release of ChatGPT, when technical specifications were stripped from the main legal text for articulating in the form of technical standards and a code of practice instead. Finding the right balance between ambitiousness and specificity, and future-proofness is no easy feat, but crucial to achieve clarity, applicability, and enforceability down the line.

A key ambiguity shared by two new laws—the DSA and the AI Act—is the requirement to conduct impact assessments, which include risks to human rights, that companies, auditors, and authorities will have to grapple with soon without clear guidance. The Commission and member states should deepen collaboration with civil society to set clear guidelines for robust and meaningful impact assessments, building on similar discussions around the European Media Freedom Act.

This also requires actionable objectives and guidelines for interpretation to ensure regulators can uphold the intended spirit of the law. For example, with the EU’s ambitious climate law, the EU Green Deal set a “climate neutrality” target instead of a “CO2 and greenhouse gas neutrality” target, effectively muddling interpretation and diverting attention from more attainable targets.

People: Invest in actors and institutions

With this wave of first-of-a-kind regulations—which will require regulators to oversee technical tasks such as conducting risk and impact assessments, analysing compliance methods, ensuring data access to researchers, and monitoring for algorithmic transparency—it will be crucial to ensure regulators and oversight bodies are sufficiently staffed and resourced, including with the technical knowledge and experience for such complex and sector specific tasks.

Just as public investments are poured into research and innovation, the EU should consider a balance between funding innovation and ensuring adequate resources for the effective enforcement of tech regulations. More effective enforcement can, in turn, incentivise innovation, which for example is the underlying driver behind competition policy in the U.S. and the EU. In addition, dedicating enough specialised people and institutions for the task will help the EU avoid potential skills shortages.

Over the next five years, how the Commission and other regulatory agencies across Europe conceive of building and supporting the knowledge and capacity required to effectively stimulate and compel the compliance of these laws will be a crucial indicator of success.

And thinking beyond this next EU mandate, the AI Office could provide a blueprint for a future EU digital enforcement agency, if it is structured with appropriate imagination and ambition. As the EU’s tech policy landscape increases in volume and complexity, such a central institution could enhance the EU’s ability to oversee such enforcement more effectively, with more technocratic candour and with a better view to cohesion.

Practice: Open-up enforcement mechanisms

EU regulators do not have to carry the enforcement burden on their own: decentralised models which distribute monitoring and oversight responsibilities can help avoid bottlenecks and enhance effective application of the rules. The Commission has been innovative thus far with the implementation of the Digital Services Act by engaging civil society through its expert group, where they can help to shape, enact, monitor, and assess the implementation of the principles outlined in this landmark platform accountability law. However, it will be crucial not to overly rely on civil society, or otherwise outsource oversight responsibilities to this sector. Adequate resourcing including stipends, honouraria, and paid contracts should be envisioned for this under-resourced sector.

There are a range of options to meaningfully open up enforcement mechanisms. Public officials can include researchers and practitioners throughout policy design, implementation and enforcement, for example, by opening up the Data Protection, Digital Services, and AI boards beyond the European Commission and member states with working groups, to be chaired independently. Such platforms for collaboration can enhance and support coordination, monitoring, and decision-making processes with broader sets of expertise, which serve to diversify and ultimately strengthen implementation and enforcement efforts and outcomes.

Beyond platforms for participation, there are many concrete ways the EU and member states can and should foster broader public oversight of tech law compliance, by increasing institutional transparency and accountability from end to end. For example, governments and institutions can adopt accessible and interoperable lobby registries, like Madrid’s, to make public decision-making more transparent and accountable; make the registration of algorithms mandatory, like the Dutch government committed to do by 2025, to ensure information about the algorithms it uses is publicly available; compel the publication of impact assessments and audit results, as is routinely done in the healthcare sector, to reinforce good compliance and enforcement practice; and expand access for researchers and monitors alike to enable a more just and transformative enforcement ecosystem.

Broadening public oversight can help ensure effective compliance and enforcement and, in turn, spark civil society agency. Organisations dedicated to advocacy, education, and media, especially, can play important roles in guiding innovation to align with public values. Researchers and practitioners can use data and evidence gathered with such tools to draw lessons, surface best practices, identify trends, and shape innovation policy. Tech journalism can foster a more knowledgeable public, and educational and ongoing training—not just in schools, but across the entire public sphere—can help close knowledge gaps and synthesise policy understanding and interpretation.

Politics: Prioritise regulatory resilience

The underlying purpose of many major regulations is two-fold: to encourage or otherwise re-align business incentives to more adequately balance business profits with democratic principles and the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights, and to safeguard against abuses of power and protect the rights of citizens within the framework of democratic governance. The power and influence of big tech is lost on no one, and it should come as no surprise that implementation and enforcement of laws cannot be seen in isolation of their surrounding political, social, and economic contexts.

For instance, many, if not all, of the world’s major tech companies have offices and data centres scattered around Europe, meaning they contribute to Europe’s economy in the forms of jobs, taxation, infrastructure, start-up ecosystems, talent development and attraction, and other economic indicators that all play a role in shaping how and where certain laws are enforced and how effective they may be. In addition, the international tech sector spends over € 113 million a year lobbying Brussels.

Regulatory resilience, then, reinforces implementation and enforcement efforts against excessive commercial interests but also against member states that might be willing to trade off fundamental rights for control, politics, or economic incentives.

This is why independence of the regulator is a crucial component of effective enforcement. Even more, court cases, market access, and press attention can contribute to an intense level of political pressure; states, regulators, and the EU generally must be ready—and willing—to stand their ground, even in the face of incredibly powerful and influential companies.

Conclusions

With the next EU leadership in sight, it is time for EU institutions and member states to level-up enforcement for a stronger digital Europe. Practically, this means Europe must prioritise effective enforcement of existing laws and ask what’s working, what needs improvement or innovating.

What should good compliance, impact assessment, implementation, and enforcement look like?

The next decade will be pivotal in reinforcing the EU’s regulatory framework, ensuring that it remains robust in the face of rapid technological change.

Stronger implementation and enforcement holds the potential to bring about a stronger Europe, which can spur more innovation and yield more regulatory soft power.

The EU is not alone in its desire to reign in big tech and ensure technologies are developed in accountable ways, so investing in, innovating and iterating new enforcement approaches in an inclusive manner could also set strong precedents for similar legislation outside of Europe. This could ultimately have a reinforcing effect on Europe’s democratic values and market principles in the world.

Conversely, weak enforcement would signal weak laws to those same global players, which could have an eroding effect on Europe’s regulatory soft power in the world.

Let’s make enforcement better together. It’s not just up to lawmakers to write good laws. It’s not just up to companies to tell authorities what’s needed. Enforcement processes can greatly benefit from the input and involvement of those with experience, knowledge and expertise, such as civil society, litigators, independent experts, citizens, and communities who are directly impacted by technology and tech-related harms.

Let’s set the bar higher, to ensure technology works for democracy in an age of accelerating innovation. What do you think comprehensive implementation and effective enforcement look like? We welcome your input and reflections on what’s here and what’s missing, as we collaboratively explore current and potential approaches, lessons learned, and develop best practices for better enforcement toward stronger public infrastructure and oversight for technology.