Preparing for AI labour shocks should be a resilience priority for Europe

The European Commission’s upcoming 2025 Strategic Foresight Report will place resilience at its core. Among many important elements of this topic, one of the most discussed is Europe’s preparedness for the scale and speed of labour market transformation driven by artificial intelligence (AI). Unlike previous waves of technology-driven disruption, AI’s reach extends beyond routine or manual labour; it is now challenging cognitive, creative, and decision-making roles that were long considered ‘safe’ areas of work. To capture the extent of potential impact and identify the true dimensions of Europe’s preparedness, stress-testing for AI-driven disruption is a critical step for the EU to take.

Summary

Challenge – AI-driven labour disruption has moved from theoretical possibility to plausible near-term scenario (for further reading, see “Beyond the AI Hype”). Just as the Industrial Revolution shifted value from human muscle to mechanical power, the AI revolution could shift value from human intelligence to machine intelligence. Unlike previous technological transitions that unfolded over decades, AI could compress workforce transformation into years while affecting cognitive and creative work previously considered automation-proof.

Implication – Europe faces a critical window in this mandate to prepare for potential AI labour shocks before they accelerate beyond manageable levels. This requires recognising automation as a cross-cutting resilience challenge affecting social protection, skills policy, fiscal systems, and democratic governance.

Action – The upcoming EU’s 2025 Strategic Foresight Report should incorporate systematic stress-testing of AI-driven labour disruption across policy domains. These stress-tests should model acceleration scenarios and translate findings into concrete preparations across social protection systems, education policy, tax policy, and democratic governance safeguards.

Introduction

While the net impact of AI on employment remains uncertain, the ingredients for large-scale disruption are increasingly falling into place: powerful new capabilities, rapidly expanding infrastructure, and declining costs of deployment. Early signs of change are already visible across a plethora of sectors. As these trends converge, the risk of destabilising labour shifts (such as wage pressure, displacement, regional inequality) moves from hypothetical to plausible. It is no longer sufficient to treat automation as a future productivity driver alone; it must also be stress-tested as a potential systemic shock.

This analysis does not predict that widespread AI displacement will occur, nor does it dismiss the potential for AI to create new employment opportunities. Instead, it argues that the conditions for rapid labour market disruption are converging in ways that make this scenario sufficiently plausible to warrant systematic preparation. When potential impacts are severe and the warning signs are accumulating, prudent risk management demands preparing for disruption even while hoping for smoother adaptation. Just as Europe prepares for potential energy supply disruptions or pandemic responses without certainty on whether they will occur, AI labour disruption merits similar contingency planning given its potential systemic impact.

The debate around AI-driven automation is highly polarised and predictions of the effects of automation range widely. Some experts predict large-scale job displacement, while others argue new roles will emerge to offset those lost. This ranges from estimates made by Daron Acemoglu, Nobel Prize-winning economist at MIT known for his research on technology and labor markets, who claims that only 5% of jobs can be automated[1], to McKinsey’s projection that by 2030, activities accounting for up to 30%[2] of work hours currently worked across the US economy could be automated, an estimate that does not even fully take into account recent AI advances. Meanwhile, economists Inga Fechner and Charlotte de Montpellier from ING Group, basing their analysis on work by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), suggest that 50.2 million Europeans, or 32% of the working population[3], are facing the risk of being replaced by AI in their current roles. On the other hand, some argue that AI could lead to many more jobs[4] and potentially revitalising the middle class. However, the International AI Safety Report (2025), representing a consensus of leading AI researchers and international organisations globally, concludes that general-purpose AI “is likely to transform a range of jobs and displace workers” with potential impacts that “could be particularly severe if autonomous AI agents become capable of completing longer sequences of tasks without human supervision.”[5].

Early signs of disruption are already visible across industries, yet deep uncertainty remains (For a comprehensive exploration of AI’s potential trajectories, see our work on possible futures of advanced AI). How far, how fast, and how widely will automation reshape the workforce? Given the stakes and the track record of AI’s rapid adoption it is crucial to rigorously assess both AI’s potential and its limits. Even if we eventually settle into a long-term equilibrium where human workers find new ways to contribute, the transition period could be highly disruptive—and worth preparing for.

Rather than defaulting to speculation or single-expert views, we need a systematic approach to understanding the drivers of automation. To begin assessing whether large-scale labour disruption is genuinely plausible, we must examine three interdependent questions:

- Does AI have the necessary capability to replace jobs?

- Are we already seeing early signs of displacement in the market?

- Will the economic and infrastructure conditions allow AI automation to scale widely?

These dimensions interact in reinforcing cycles: Rapid capability advances drive market adoption, which justifies infrastructure investments that further reduce costs and accelerate development. The following sections address each question in turn, building toward an integrated assessment of Europe’s preparation needs.

1. Can AI replace jobs?

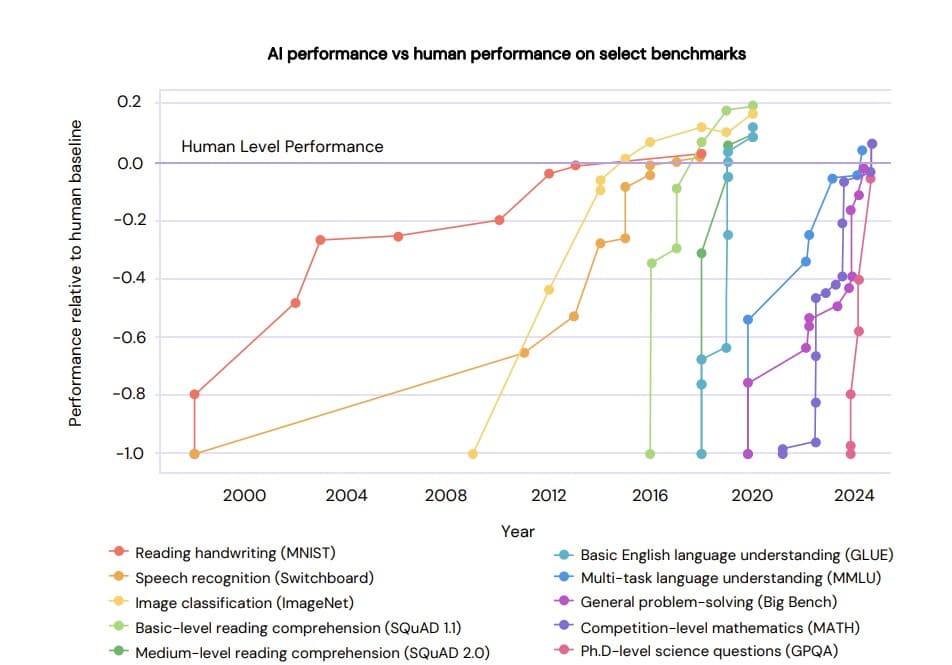

AI capabilities are evolving at an extraordinary pace (see Figure 1), rapidly approaching the point where they could automate a vast range of cognitive and creative tasks. This acceleration has caught even senior policymakers off guard, as European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen recently acknowledged: “When the current budget was negotiated, we thought AI would only approach human reasoning around 2050. Now we expect this to happen already next year.“

AI is already outperforming human doctors on medical diagnosis[6], increasing research output[7], and boosting consultants’ working speed and output quality[8], while advanced AI agents are beginning to handle complex real-world decision-making. Unlike previous waves of automation, which primarily affected routine manual jobs, AI now starts to affect professional roles that were once considered uniquely human. For instance, almost 3000 researchers in the field surveyed by AI Impacts estimate that AI can perform most professional tasks that humans do before 2035[9]. While AI’s current reliability varies, its improvement trajectory[10] suggests that within the next few years, large segments of knowledge work could be replicated.

Large-scale labour displacement from AI automation is increasingly plausible because of the unprecedented speed of AI progress. Breakthroughs like autonomous AI “agents” capable of complex decision-making look to be moving from research labs to real-world applications. OpenAI is developing ‘Operator,’[11] an AI agent capable of automating multi-step tasks like coding and scheduling, while Google’s ‘Astra’ and ‘Mariner’ streamline tasks across devices and browsers, making AI assistants increasingly mainstream[12]. In enterprise settings, ServiceNow’s AI agents autonomously manage up to 80% of customer service, HR, and IT interactions, cutting costs and boosting efficiency[13]. Recently Anthropic’s Lead Engineer, revealed that 80% of the code of their popular AI model Claude is now generated by Claude[14]. The International AI Safety Report found that AI agents ”have the potential to affect workers more significantly than general-purpose AI systems that require significant human oversight” because they can “chain together multiple complex tasks, potentially automating entire workflows rather than just individual tasks.”[15].

The Industrial Revolution’s displacement unfolded over decades, allowing gradual adaptation—and nevertheless caused many growing pains. Given what we’ve already seen from AI expanding automation into the cognitive and social domains, it’s increasingly likely that AI could condense decades of workforce transformation into just a few years.

2. Is displacement already underway?

We are already seeing labour market impacts from AI at the company level, with evidence suggesting these effects might intensify. AI-driven disruption is now observable across multiple sectors. In Germany, TikTok content moderators went on strike in July 2025 over concerns that AI was replacing their jobs, highlighting how automation anxieties are spreading beyond tech hubs to workers across Europe[16].Companies like IBM have paused hiring for thousands of back-office positions identified as AI-replaceable. Consumer companies are restructuring around AI capabilities, with Duolingo announcing plans to ‘gradually stop using contractors to do work that AI can handle’ and requiring teams to prove AI cannot perform a role before hiring humans[17].

Beyond direct layoffs, some hiring patterns are also shifting. Organisations using AI post 12% fewer non-AI job vacancies, suggesting a structural change in workforce planning. Lastly, PwC research indicates that one in four CEOs plan to reduce their workforce by at least 5% in the coming year due to generative AI, the evidence strongly suggests that AI-driven labour market transformation is already underway in several key sectors, and might be accelerating.

Adoption Rates of Various Technologies and Modern AI

This figure illustrates that modern technologies are being adopted at an increasingly rapid pace, with AI adoption standing out as exceptionally fast. Source: Our World in Data (for all technologies except AI), Pew Research (for ChatGPT usage), Bick et al. 2024 (for the working US population), and YouGov (for US population using AI occasionally).

Despite these company-level shifts, European macroeconomic data does not yet show evidence of widespread AI-driven labour disruption. EU unemployment stands at just 5.8% as of 2025, down from 6.0% a year earlier. Youth unemployment has also declined across the EU, suggesting that even entry-level work, often considered most vulnerable to AI automation, continues to provide employment opportunities to most.

This isn’t necessarily at odds with the disruption already visible at the company level—macroeconomic indicators tend to lag behind firm-level changes, especially during the early stages of technological transitions. But that lag doesn’t make it wise to wait. If disruption is already underway beneath the surface, waiting for it to show up in aggregate data could mean missing the window for proactive response.

3. Economic conditions for widespread adoption

While these early market signals indicate that AI displacement is beginning, the scale of future disruption will hinge on whether current adoption spreads more widely across the economy. Even if AI gets good enough—and reliable enough—for people to actually trust it with real tasks, it won’t be used widely unless at least two things are in place: enough computing power, and this compute needs to be cheap enough to automate tasks at scale.

Massive infrastructure investments are creating the computational foundation necessary for AI automation to scale across the economy. Private investment in AI hardware is surging, with Big Tech leading the charge. In the first three quarters of 2024, Microsoft, Meta, Alphabet, and Amazon spent nearly $170 billion on AI[24]—up 56% from the same period in 2023—putting them on track to invest over a quarter of a trillion dollars in AI infrastructure in 2025. Additionally, OpenAI, SoftBank, Oracle, and MGX have launched Stargate[25]—a plan to invest $100 billion annually for the next four years to build AI data centres—backed by the Trump administration. Together, these efforts make it increasingly plausible that the necessary compute infrastructure for widespread automation could soon be in place.

For AI to replace human workers at scale, it must be financially viable. So far, AI training and deployment costs have been significant— training a state-of-the-art language model can cost millions of dollars solely in cloud computing[26], not to mention the high salaries of researchers and engineers. Many AI companies operate as “labs,” focusing on exploratory research that often requires hundreds of millions—or even low billions[27]—in investment to build cutting-edge models. Recent developments in AI have led to the introduction of models with subscription fees surpassing typical human salaries. Notably, OpenAI plans to offer specialised AI agents, including one designed for PhD-level research, at a monthly rate of $20,000.

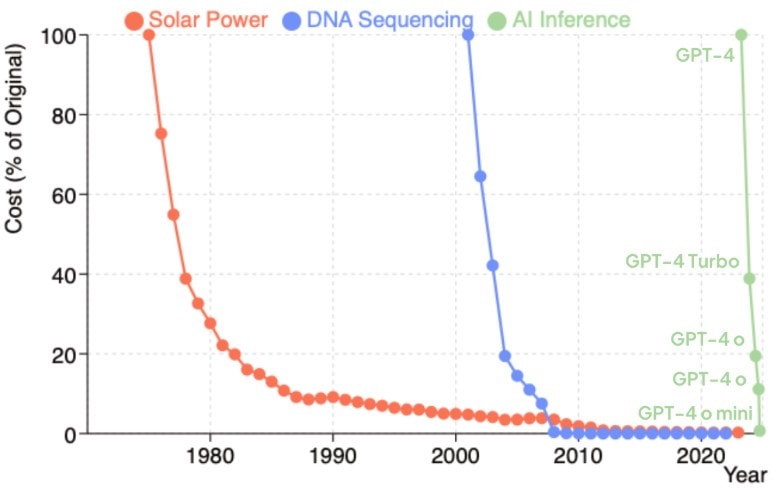

However, prices are dropping fast (see Figure 3). The cost of running advanced models has dropped sharply thanks to cheaper compute, optimised architectures, and growing economies of scale. Alongside the significant decline in cost of AI usage, the technique of model distillation has emerged as a pivotal factor in reducing expenses (from early general theory[28] to current applied theory[29]). This process involves transferring knowledge from larger, complex models to smaller, efficient ones, thereby maintaining performance while lowering computational requirements and costs. An example of this is the notorious DeepSeek R1 model[30], developed by the Chinese startup DeepSeek, which has achieved capabilities comparable to leading AI systems at a fraction of the cost. This efficiency is largely attributed to the application of knowledge distillation techniques, enabling the creation of a powerful yet cost-effective model. Such advancements suggest that, despite the high initial pricing of new AI models, similar cost reductions could be achieved through distillation and other optimisation methods.

Data sources: Solar power: Our World in Data – Solar PV Prices, DNA sequencing: Our World in Data – Cost of Sequencing a Human Genome, AI inference: OpenAI’s Dane Vahey’s presentation recording shared by Tsarathustra on X, data can be checked on OpenAI’s pricing page history.

These efficiency gains follow a well-established pattern in technology adoption known as Wright’s Law, the principle of which is: the more we produce something, the better we get at making it cheaply[31]. As Michael Liebreich notes in his analysis of AI and energy, the efficiency gains in AI have been remarkable—with Nvidia claiming “a 45,000 improvement in energy efficiency per token” over just eight years[32], demonstrating how rapidly AI technology can evolve when driven by competitive pressures. If this trend continues to hold for AI, the economic case for replacing human labour with AI could become extremely compelling.

4. How should Europe prepare?

This analysis makes a case for elevating AI labour disruption from a speculative concern to an active planning priority. The convergence of rapidly advancing capabilities, early market displacement signals, and massive infrastructure investments suggests that AI-driven labour disruption has moved from theoretical possibility to plausible near-term scenario. Europe faces a critical window to prepare for potential AI-driven labour disruption before it might accelerate beyond manageable levels. This demands proactive preparation across multiple policy domains rather than focusing largely on responses to crises already underway. While automation offers enhanced competitiveness and potential relief for Europe’s aging workforce, it also carries multifaceted implications extending far beyond immediate employment concerns, including social cohesion challenges, and an unprecedented rate of skills obsolescence.

The EU’s 2025 Strategic Foresight Report should incorporate AI labour disruption as a core resilience challenge through systematic stress testing across policy domains. Rather than treating automation as an isolated employment issue, these stress tests should model acceleration scenarios where 50% of knowledge work becomes automatable within 3-5 years rather than the commonly assumed 20-25 years. These areas are examples of what requires examination:

- Social protection systems: Can unemployment benefits and retraining programs handle sudden displacement across finance, administration, and professional services simultaneously?

- Education and skills policy: How quickly can curricula adapt when entire degree programs lose market relevance? What mechanisms exist for rapid skill certification and career transitions?

- Tax and fiscal policy: Will current revenue models remain viable if corporate productivity surges while employment drops? How can automation dividends be fairly distributed?

- Democratic governance: What safeguards prevent political instability if automation’s benefits concentrate among capital owners while workers face widespread uncertainty?

- Economic sovereignty and geopolitical resilience: Can Europe regain its competitive edge and strategic autonomy in a world where economic gains increasingly accrue to those able to build AI infrastructure more efficiently, more cheaply, and at greater scale?

Large portions of the economy could move from human heads to automated data centers and AI systems. Just as the Industrial Revolution shifted value from human muscle to mechanical power, the AI revolution shifts value from human intelligence to machine intelligence. The economic winners will be those that build and control this cognitive infrastructure at scale.

The goal is not to predict the future but to ensure Europe is resilient across multiple plausible futures. If AI’s labour market impact proves gentler than outlined here, robust social protection and adaptive institutions will serve Europe well regardless. If disruption accelerates as this analysis suggests is plausible, early preparation could mean the difference between managing a transition and experiencing a crisis.

Endnotes

[1] Wittenstein, Jeran. “AI Can Only Do 5% of Jobs, Says MIT Economist Who Fears Crash.” Bloomberg, 2 Oct. 2024. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-10-02/ai-can-only-do-5-of-jobs-says-mit-economist-who-fears-crash

[2] Ellingrud, Kweilin, et al. “Generative AI and the future of work in America.” McKinsey, 26 Jul. 2023. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/technology-media-and-telecommunications/our-insights/generative-ai-and-the-future-of-work-in-america

[3] Fechner, Inga, and Charlotte de Montpellier. “AI will fundamentally transform the job market but the risk of mass unemployment is low.” ING Think, 21 Mar. 2024. https://think.ing.com/articles/ai-will-fundamentally-transform-job-market-but-risk-of-mass-unemployment-is-low/#a2

[4] Autor, David. “AI could actually help rebuild the middle class.” Noema Magazine, 12 Feb. 2024. https://www.noemamag.com/how-ai-could-help-rebuild-the-middle-class/

[5] International AI Safety Report, “Chapter 2.3.1. Labour market risks,” UK AI Safety Institute, 2025, pp. 111-118. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/679a0c48a77d250007d313ee/International_AI_Safety_Report_2025_accessible_f.pdf

[6] Goh, E, Gallo R, Hom J, et al., Large Language Model Influence on Diagnostic Reasoning: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(10):e2440969. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.40969, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2825395

[7] Aidan Toner-Rodgers, Artificial Intelligence, Scientific Discovery, and Product Innovation, 2024, https://conference.nber.org/conf_papers/f210475.pdf

[8] Dell’Acqua, F., et al., “Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality. ” Harvard Business School Working Paper, No. 24-013, September 2023, https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=64700

[9] Grace, Katja. “Survey of 2,778 AI authors: six parts in pictures.” AI Impacts Blog, 4 Jan. 2024. https://blog.aiimpacts.org/p/2023-ai-survey-of-2778-six-things

[10] E.g. On the TruthfulQA benchmark, which assesses the accuracy of AI-generated information, the top-performing AI model improved significantly, from 58% accuracy when the benchmark was introduced in 2022 to 91.1% by January 2025, approaching the 94% accuracy achieved by humans – Lin, Stephanie, Jacob Hilton, and Owain Evans. “TruthfulQA: Measuring How Models Mimic Human Falsehoods.” arXiv, 2022

Falsehoods, 2021, https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.07950; LessWrong, New, improved multiple-choice TruthfulQA, https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/Bunfwz6JsNd44kgLT/new-improved-multiple-choice-truthfulqa

[11] Jak Connor, “OpenAI’s new ‘Operator’ touted as the next breakthrough in artificial intelligence”, TweakTown, 2025, https://www.tweaktown.com/news/102708/openais-new-operator-touted-as-the-next-breakthrough-in-artificial-intelligence/index.html

[12] Roula Khalaf, “Google races to bring AI-powered ‘agents’ to consumers”, Financial Times, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/96ba29e6-cbc2-4da0-917b-8a2545c1cd00

[13] John Kell, “How software companies are developing AI agents and preparing their employees for the next wave of generative AI”, 2025 https://www.businessinsider.com/generative-ai-evolution-software-companies-develop-ai-agents-workforce-2025-3

[14] Boris Cherny. “Claude Code: Anthropic’s CLI Agent ” YouTube, uploaded by Latent Space, May 7, 2025. https://youtu.be/zDmW5hJPsvQ?si=28SijEt1ZRfdnfLx&t=1097

[15] International AI Safety Report, “Chapter 2.3.1. Labour market risks,” UK AI Safety Institute, 2025, pp. 111-118. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/679a0c48a77d250007d313ee/International_AI_Safety_Report_2025_accessible_f.pdf

[16] TikTok Content Moderators in Germany Strike Over AI Taking Their Jobs’, Euronews (23 July 2025), https://www.euronews.com/next/2025/07/23/tiktok-content-moderators-in-germany-strike-over-ai-taking-their-jobs

[17] Katie Notopoulos. “Duolingo drama underscores the new corporate balancing act on AI hype.” Business Insider, 21 May 2025. https://www.businessinsider.com/ai-messaging-backlash-duolingo-shopify-controversy-2025-5?international=true&r=US&IR=T

[18] Our World in Data. “Share of United States households using specific technologies.” Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/technology-adoption-by-households-in-the-united-states

[19] Pew Research Center. “Americans increasingly using ChatGPT, but few trust its 2024 election Information.” Pew Research Center, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/03/26/americans-use-of-chatgpt-is-ticking-up-but-few-trust-its-election-information/

[20] Bick, A., et al. “The Rapid Adoption of Generative AI.” 2024. https://889099f7-c025-4d8a-9e78-9d2a22e8040f.usrfiles.com/ugd/889099_84dd647ce02de95.pdf

[21] YouGov. “Do Americans think AI will have a positive or negative impact on society?” YouGov, 2025, https://today.yougov.com/technology/articles/51368-do-americans-think-ai-will-have-positive-or-negative-impact-society-artificial-intelligence-poll

[22] “Unemployment statistics.” Eurostat, March 2025. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Unemployment_statistics

[23] The Economist. “Why AI hasn’t taken your job.” The Economist, 26 May 2025. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2025/05/26/why-ai-hasnt-taken-your-job

[24] Forbes. “AI Spending To Exceed A Quarter Trillion Next Year.” Forbes, 2024, https://www.forbes.com/sites/bethkindig/2024/11/14/ai-spending-to-exceed-a-quarter-trillion-next-year/?ref=platformer.news

[25] Financial Times. “Stargate artificial intelligence project to exclusively serve OpenAI” Financial Times, 2025, https://www.ft.com/content/4541c07b-f5d8-40bd-b83c-12c0fd662bd9

[26] Cottier, B., et al., The rising costs of training frontier AI models, 2025, https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.21015

[27] Epoch AI. “How Much Does It Cost to Train Frontier AI Models?” Epoch AI, 2024, https://epoch.ai/blog/how-much-does-it-cost-to-train-frontier-ai-models

[28] Hinton, Geoffrey, Oriol Vinyals, and Jeff Dean. “Distilling the knowledge in a neural network.” arXiv, 9 Mar. 2015. https://arxiv.org/abs/1503.02531

[29] Boix-Adserà, Enric. “Towards a theory of model distillation.” arXiv, 7 May 2024. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2403.09053

[30] Knight, Will. “DeepSeek’s new AI model sparks shock, awe, and questions from US competitors.” Wired, 28 Jan. 2025. https://www.wired.com/story/deepseek-executives-reaction-silicon-valley/

[31] ARK Invest, ‘Moore’s Law Isn’t Dead: It’s Wrong – Long Live Wright’s Law’, ARK Investment Management LLC (2 January 2019), https://www.ark-invest.com/articles/analyst-research/wrights-law-2

[32] Liebreich, Michael, ‘Generative AI – The Power and the Glory’, BloombergNEF (24 Dec 2024), https://about.bnef.com/insights/clean-energy/liebreich-generative-ai-the-power-and-the-glory/